사용자:Jjw/작업장3

싱가포르의 역사는 14세기 싱가포르섬에 세워진 싱가푸라 왕국까지 거슬러 올라가지만, 현대의 싱가포르는 19세기 영국령 싱가포르에서 출발하였다. 말레이반도와 수마트라섬 사이의 믈라카 해협 입구에 위치한 때문에 동남아시아 해상 무역의 거점으로 성장하였다.

제2차 세계대전 기간인 1942년에서 1945년 사이 싱가포르는 일본제국에 점령되었다. 일본 제국이 항복한 뒤 싱가포르는 다시 영국령으로 귀속되었으나 자치를 요구하는 목소리가 커졌고 1963년 말레이시아가 독립하면서 싱가포르주로 말레이시아의 행정 구역에 편입되었다. 그러나 싱가포르의 다수당인 인민행동당은 말레이시아 편입을 거부하고 1965년 8월 9일 독립공화국을 수립하여 현재까지 이어지고 있다. 인민행동당은 독립 이후 지금까지 계속하여 여당의 지위를 유지하였다.

1961년 있었던 부킷호스위 화재를 계기로 싱가포르에 만연해 있던 높은 실업률과 주거 불평등이 사회 문제로 부각되었고 1960년대에서 1970년대를 거치며 산업화를 통한 고용 창출과 높은 교육율, 그리고 공공 주택 공급을 통한 주거 문제 해결을 특징으로 하는 싱가포르 현대화가 추진되었다.

1990년대에 들어 국제 무역의 거점이라는 지정학적 특징에 맞추어 자유 시장 경제를 내세운 싱가포르는 경제 발전에 힘입어 세계에서 가장 번영하는 국가 가운데 하나가 되었다. 지금도 싱가포르는 1인당 명목 GDP 순위에서 아시아에서 가장 높은 순위를 보이며[1] 세계 전체에서도 7위를 차지하고 있다. UN의 인간 개발 지수 순위에서도 최상위권이다.[2][3][4]

고대 싱가포르

편집고대 그리스-로마 시기에 말레이반도는 막연하게 나마 "황금 반도"(고대 그리스어 Χρυσῆ Χερσόνησος, 크리세 케르소네소스)로 알려져 있었으며 프톨레마이오스는 싱가포르에 해당하는 지역을 반도의 끝이란 의미에서 "사바나"라고 불렀다.[5] 3세기 무렵 중국은 싱가포르섬을 포라중(蒲羅中)으로 기록하고 있다. 이는 말레이어의 "풀라우 우종(Pulau Ujong, 끄트머리 섬)을 음사한 것이다..[6]

7세기에서 10세기 무렵 싱가포르는 말레이반도와 수마트라를 비롯한 동남아시아 해역을 장악하고 있던 스리위자야의 지배 아래 있었다. 1025년 남인도를 근거지로 하고 있던 촐라의 라젠드라 1세가 인도양을 건너스리위자야를 침공하였다.[7][8] 촐라는 싱가포르섬에 있던 테마세크(Temasek)를 수십 년 동안 점령하였는데[9] 이 이름은 중국에서 단마석(單馬錫)이라고 음차하였다.[10] 그러나 촐라의 테마세크 점령은 촐라측 기록엔 남아있지 않고 《말레이 연대기》에 언급되어 있다.[11] 자바섬 출신의 시인 나가라크레타가마이 1365년 쓴 서사시는 싱가포르섬에 세워진 도시를 "투마시크"라고 표기하고 있는데 아마도 "항구"를 뜻하는 말일 것으로 보인다.[12]

《말레이 연대기》는 스리위자야의 왕자 스리 트리 부와나(상 닐라 우타마)가 13세기 무렵 테마세크를 세웠다는 이야기가 수록되어 있다. 스리 트리 부와나가 사냥을 떠나 싱가포르섬에 상륙하여 보니 낮선 짐승이 있었는데 주민들이 그것을 사자라고 부렀다고 한다. 스리 트리 부와나는 이를 상서로운 징조로 여기고 도시를 세우고 사자의 도시 즉, "싱가푸라"라고 불렀다고 한다. 이 이야기는 널리 알려진 싱가포르의 기원이지만 실제 싱가포르의 어원이 무엇인지는 확실하지 않다.[13]

1320년 몽골 제국은 오늘날 케펠항에 해당하는 롱야먼(龍牙門, 용아문)으로 무역 사절을 파견하였다.[14] 1330년 무렵 중국의 여행가 왕다유안(汪大渊, 왕대연)이 싱가포르섬을 방문하고 롱야먼이 테마세크와 말레이반도의 반주(班卒, 반졸]] 사이에 있다고 기록하였다. 반주는 오늘날 포트 캐닝힐 자리에 있었을 것으로 추정된다. 싱가포르 고고학회는 개닝 힐 요새를 발굴하고 14세기 무렵 이 자리가 중요한 무역 거점이었음을 밝혔다.[15][16] 왕다유안은 롱야먼에 싱가포르섬 원주민인 오랑 라우트와 중국에서 이주해 온 사람들이 함께 살고 있었다고 기록하였다.[17][18] 싱가포르는 가장 먼저 중국 밖에 화교 사회가 형성된 지역들 가운데 하나로서 많은 고고학적 발굴 및 역사 연구가 있어왔다.[19]

14세기 무렵이 되면 스리위자야는 이미 멸망하였고 싱가포르섬을 비롯한 말레이반도는 시암(오늘날의 태국)과 마자파힛 제국 사이의 각축장이 되었다. 《말레이 연대기》는 마자파힛이 싱가포르섬을 공격하여 점령하였으나 몇 년 후 세워진 믈라카 술탄국이 말레이반도 전역과 싱가포르섬에 대한 지배권을 행사하였다고 기록하고 있다.[20] 그러나 포르투갈의 기록에는 팔렘방이 거점이었던 팔라메스와라 술탄이 데마세크의 시암인 지배자를 죽였고 그가 믈라카 술탄국을 세웠다고 언급하고 있다.[21] 오늘날 고고학 발굴 결과는 이 무렵 포트 캐닝의 거주지는 폐허가 되었지만 싱가포르섬에는 작은 규모의 무역 거점이 이후로도 계속 이어졌다는 것을 보여준다.[13] 오늘날 말레이시아의 믈라카주가 중심지였던 믈라카 술탄국은 점차 영토를 확장하여 말레이반도와 싱가포르섬 그리고 인근 다른 섬들까지 지배하게 되었다.[6]

16세기 무렵 포르투갈이 동남아시아 해역에 들어왔을 당시 싱가포르는 이미 쇠락한 상태였다. 아폰수 드 알부케르크는 싱가포르섬에 대해 "거대한 폐허"만이 있다고 기록하였다.[22][23] 1511년 포르투갈은 믈라카 술탄국을 침공하였고 믈라카가 함락되자 술탄은 도피하여 조호르 술탄국을 세웠다. 싱가포르섬은 이후 조호르 술탄국의 지배를 받았다. 1613년 포르투갈은 싱가포르섬을 점령하였고 이후 2세기 동안 이슬람은 싱가포르에 들어서지 못하였다.[24][25]

1819년: 영국령 싱가포르

편집16세기에서 19세기 사이 말레이 제도는 유럽 제국주의 국가들의 식민주의가 횡행하였다. 첫발을 디딘 곳은 1509년 믈라카에 도착한 포르투갈이었고 17세기엔 네덜란드 동인도회사의 식민지 점령이 시작되었다. 네덜란드는 말레이 제도의 중요 항구를 거의 모두 점령하여 네덜란드 식민제국으로 삼았다. 네덜란드는 동남아시아의 향신료 플랜테이션을 독점하여 막대한 부를 거머쥐었다. 한편 네덜란드의 사례를 본 영국도 영국 동인도 회사를 세우고 인도 아대륙에 대한 식민 점령을 시작하였으나 동남아시아 지역에서 영국의 영향력은 제한적이었다.[26]

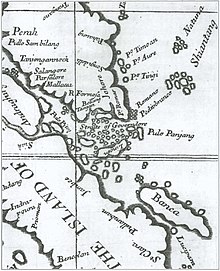

1818년 토머스 스탬퍼드 래플스는 동남아시아 지역에 대한 영국 동인도 회사의 식민지인 영국령 븡쿨루의 부총독으로 임명되어 말레이 제도에서 네덜란드의 영향력을 약화시키고 영국이 그 자리를 대체하기로 마음 먹었다. 그는 당시 영국 제국의 주요 무역로였던 인도와 중국 사이의 항로의 결정적 위치에 영국 소유의 항구를 만들기로 결심한다. 당시 동남아 지역에서 영국 소유의 항구는 말레이반도 서안의 피낭이 유일하였다.[26]

1819년 1월 28일 싱가포르에 도착한 래플스는 믈라카 해협에 인접한 이곳이 자신이 구상한 새 항구를 세울 적지라고 직감하였다. 싱가포르섬은 식수도 충분하였고 숲이 울창하여 선박을 수리할 목재를 구하기도 쉬웠다. 무엇보다 인도와 중국 사이를 왕복하는 무역로는 반드시 싱가포르 앞바다를 지나야만 하였다. 래플스가 싱가포르강 하구에서 새 항구 건설지를 무색하고 있을 당시 그곳에는 대략 150명의 말레이 인과 30여 명의 중국인이 거주하고 있었다.[27] 이 지역을 관리하고 있던 세력은 조호르 술탄국이 파견한 관리인 테멘궁과 1811년 조호르에서 건너온 1백여 명의 말레이 인이었다.[27] 그 외에 오랑 라우트와 같은 원주민까지 합쳐 당시 싱가포르섬의 전체 인구는 1천 명 가량이었다.[28] 싱가포르섬은 명목상 조호르 술탄국의 영토였지만 당시 조호르는 네덜란드의 지배 아래에 있었다. 또한 조호르는 술탄인 후세인 샤와 그의 동생 텡쿠 압둘 라흐만 사이의 알력으로 지배층이 분열되어 있었다. 래플스는 둘 사이의 알력을 이용하여 술탄 후세인 샤에게 연공으로 5천 스페인 달러를 그리고 싱가포르의 총독 격인 테멩공 에게 3천 스페인 달러를 지불하고 싱가포르의 관할권을 사들였다. 후세인 샤는 그 댓가로 영국이 싱가포르에 무역항을 건설하는 것을 허가하였다.[26] 1819년 2월 6일 조약이 채결됨에 따라 싱가포르에 무역항이 세워지게 되었다.[29][30]

래플스가 처음 싱가포르에 도착 했을 당시 인구는 대부분 말레이인으로 1천여 명 정도였고 수십 명의 중국인이 있을 뿐이었지만[31][32] 근대적인 중계 항구가 되면서 인구는 급격히 증가하여 첫 인구 조사가 이루어진 1824년에는 10,683 명이 되었으며 이 가운데 6,505 명은 말레이족과 부기족이었다.[33] 영국이 항구를 건설한 지 몇 달 지나지 않은 때부터 다수의 중국인 이민이 시작되었다. 1826년 인구 조사 때는 이미 중국인의 인구가 말레이족의 수를 넘어서 부기족과 자와인 다음의 3위에 올라서 있었다.[34] 싱가포르의 이민과 인구 성장은 꾸준히 지속되었으며 이민자들은 주로 말레이반도, 중국, 인도 등지 출신이었다. 1871년 싱가포르 인구는 10만 명을 바라보게 되었고 이 가운데 절반은 중국인이었다.[35]

중국이나 인도에서 건너 온 초기 이민자들은 주로 플랜테이션이나 주석 광산에서 일하는 노동자였다. 이들은 몇 년 동안 일하여 돈을 모으면 다시 자신의 고향으로 돌아가려는 희망으로 남성 노동자 혼자 싱가포르로 들어온 경우가 많았다. 그러나 싱가포르가 성장한 이후인 20세기 초에서 중반 사이의 이민은 앞 세대와 달리 온 가족이 함께 영구적으로 정착하고자 하는 경우가 대부분으로 이들과 그 후손이 현재 싱가포르 인구의 반 이상을 차지하고 있다. [36][37]

1819–1826년: 성장 초기

편집래플스는 싱가포르 조약을 채결 한 뒤 곧바로 자신의 집무지인 븡쿨루로 귀환하였고 후속 조치는 윌리엄 파커(William Farquhar) 대령의 관할 아래 이루어졌다. 아무 것도 없는 상태에서 항구를 건설하는 일은 매우 힘든 사업이었다. 싱가포르를 경제자유구역인 자유항으로 두려는 패플스의 계획에 따라 파커는 항구를 드나드는 수송선에 대해 아무런 세금을 징수할 수 없었다. 파커는 세인트 존스 아일랜드에 사무실을 세우고 믈라카 해협을 지나는 선박들이 싱가포르에 기항할 수 있도록 지원하는 한편 세수를 위해 이민 장려 정책을 실시하였다.

1819년 싱가포르를 경유한 무역량은 40만 스페인 달러였지만 몇 년 뒤인 1821년 싱가포르의 인구는 약 5천여 명으로 늘었고 무역량은 8백만 달러로 급증하였다. 1824년 인구가 1만 명을 넘어서고[33] 무역량이 2천2백만 달러에 이르면서 싱가포르는 장기간 유지될 수 있는 자생력을 갖추기 시작하였다.[26]

래플스는 1822년 10월 싱가포로 돌아와 파커가 내린 많은 결정들을 재검토 하였다. 초기 항구 건설의 어려움 속에서도 파커는 비교적 괜찮은 지도력을 발휘하였으나 래플스가 생각하는 도시 발전과는 다른 정책들이 많았기 때문이다. 파커는 세수 확보를 위해 도박장과 아편 판매를 허용하였고 노예 무역과 무기 암거래를 눈감아 주고 있었다. 이로 인해 싱가포르는 도박과 아편이 만연한 도시가 되어 가고 있었으며 래플스는 파커의 이러한 조치들을 취소하였다.[38] 래플스는 파커의 지위를 해제하고 그 자리에 존 크로퍼드를 임명하였다.[39]

래플스는 싱가포르의 도시 계획을 수립하였다.[26] 1823년 6월 7일 새 행정관이 된 존 크로퍼드는 싱가포르에 대한 권한을 놓고 조호르의 술탄 그리고 술탄국의 명목상 싱가포르 총독인 테멩공과 2차 조약을 추진하였다. 크로퍼스는 매월 종신 연금으로 술탄에게 1500 달러, 그리고 테멩공에게 800 달러를 지불하기로 하고 싱가포르의 조세 수취권을 비롯한 대부분의 권리를 매입하였다. 이 조약에 따라 싱가포르는 기존의 말레이 관습이나 샤리아가 아닌 영국법에 의해 지배되었다.[26] 1823년 10월 래플스는 영국으로 귀환하였고 몇 년 뒤 사망하였다.[40] 한편 1824년 싱가포르는 조호르 술탄국의 주권이 완전히 부정되고 영국 동인도 회사에 귀속되었다.

1826–1867년: 해협식민지

편집영국이 싱가포르에 대한 지배력을 확보하자 네덜란드는 이를 동아시아 네덜란드 식민 제국에 대한 위협으로 여겼고 영국이 계속하여 싱가포르를 지배할 수 있을 지는 의심스러웠다. 그러나 싱가포르가 매우 중요한 거점 항구로 발전하자 영국은 싱가포르에 대한 지배를 영속화하고자 하였다. 둘은 1824년 영국-네덜란드 조약을 통해 싱가포르에 대한 영국의 지배를 인정하고 말레이반도 북부를 포함한 믈라카 해협 전체를 두 나라의 공동 관리 아래 두기로 합의하였다. 1826년 싱가포르는 영국 동인도 회사가 지배하는 해협식민지의 일원이 되었다. 1830년 영국 동인도 회사는 싱가포르를 다른 해협식민지들과 함께 영국 동인도 회사의 "자산"으로서 벵갈 지구로 편입하였는데 이는 이후 영국령 인도 시기까지 유지되었다.[41]

이 시기 싱가포르가 믈라카 해협의 중요한 거점 항구로 성공한 원인으로는 다음의 몇 가지를 꼽을 수 있다. 인도와 중국 사이를 왕복하는 필수적인 항로였고 때마침 도입된 증기선의 출현으로 해상 무역량이 증가하였으며 1869년 수에즈 운하가 개통되자 유럽까지의 수송 비용이 극적으로 낮아져 해운 수요가 더욱 커졌기 때문이다.[42] 또한 결국 말레이반도 대다수를 식민지로 만드는 데 성공한 영국이 세운 영국령 말라야에서 생산되는 고무 역시 산업화의 진전과 함께 수요가 폭발하였다.[43]

한편 싱가포르의 경쟁 항구인 바타위아(오늘날의 자카르타)나 마닐라는 여전히 출입 선박에 대해 세금을 부가하고 있었기 때문에 별도의 세금이 없는 자유항인 싱가포르가 더욱 경쟁력을 지닐 수 있었다. 이 때문에 영국 선박 뿐만아니라 인도나 이슬람, 중국 상선들도 다른 곳 보다 싱가포르를 선호하였다. 수에즈 운하가 개통되자 싱가포르의 연간 화물 유통량은 더욱 급증하여 1880년 1백5천만 톤에 이르렀다. 이 가운데 증기선 수송량은 약 80% 정도였다.[44] 싱가포르 상업 활동의 근간은 중계무역으로 수입된 화물은 통관 절차 없이 보세구역에서 바로 다시 수출되었다. 이 때문에 국제 무역상은 약간의 수수료와 창고 비용만으로 무역 수익을 올릴 수 있었다. 예를 들어 인도에서 온 화물선은 싱가포르에서 화물을 내리고 중국산 화물을 되실어 인도로 돌아가는 것이 직접 중국을 왕복하는 것 보다 이익이 크다. 당시 싱가포르를 출입하는 상선은 대부분 유럽 상사 소속이었지만 중국의 양행(洋行)을 비롯하여 아랍, 아메리카, 인도 등 세계 각지의 선박이 싱가포르로 몰렸다.[41]

1827년이 되자 중국인이 싱가포르 주민 가운데 가장 많은 인구를 차지하게 되었다. 이들 중국인의 후손은 현지 주민과 섞이면서 프라나칸 또는 바바뇨냐(민난어峇峇娘惹)로 불리게 되었다. 중국인들은 상업에 종사하는 상인들과 노동자로 일하는 쿨리 같이 다양한 계층이 있었다. 1839년 - 1842년 사이의 제1차 아편 전쟁과 1856년 - 1860년 사이의 제2차 아편 전쟁 기간 동안 중국인의 수는 감소하였지만 전쟁이 끝나자 중국인의 수는 곧바로 더 늘어났다.

말레이족은 싱가포르에서 두 번째로 인구가 많은 사람들로 어부에서 장인을 비롯하여 각양 각종의 일에 종사하였다. 이들은 말레이어로 항구를 뜻하는 "캄풍"이라 불리는 지역에 몰려 살았다. 1860년 이후 인도에서 일거리를 찾아 이민자가 몰려왔다. 이들은 각종 비숙련 노동에 종사하였다. 또한 세포이 역시 영국 동인도 회사의 병력으로서 싱가포르에 들어왔다.[41]

이처럼 싱가포르는 급격히 성장하면서 다양한 출신 배경을 갖는 사람들이 섞여 살아가는 복잡한 도시로 발전하고 있었지만 영국 당국의 관심은 무역항의 유지와 수익에 있을 뿐 도시 자체에 대한 공공 행정에 신경을 쓰지는 않았다. 이 시기 세계는 처음으로 전 세계가 동시에 같은 질병으로 고통받는 펜데믹을 겪었다. 콜레라와 천연두가 전 세계에 만연한 것이다. 싱가포르도 1830년에서 1867년 사이 이 질병으로 큰 고통을 겪었다. 그러나 주민들은 공공 의료 서비스를 전혀 기대할 수 없었다. 싱가포르의 규모는 급격히 증가하였지만 영국 동인도 회사의 관리 인력 수는 제자리 였고, 더욱이 책임자는 싱가포르가 아니라 멀리 동인도 회사 본부에 앉아 있었다.[41] 행정 공백으로 막지 못하여 창궐한 역병에 주로 임시로 거주하는 일용직 남성 노동자가 희생되었고 도시는 무법 천지의 혼란 속으로 빠져들었다. 1850년 싱가포르의 인구는 대략 6만 여명이었지만 경찰관은 고작 12명에 불과하였다. 이 때문에 매춘과 도박 그리고 아편이 만연하였다. 오늘날 삼합회의 전신인 중국계 폭력 조직은 조직원이 1만 명이라는 소문이 돌 정도로 성장하였다. 이들은 경쟁자와 전쟁을 일삼았고 수 백명의 조직원이 살해 당하기도 하였다.[45]

도시의 상황이 최악으로 치달으면서 유럽계 주민들이 떠나기 시작하였다. 1854년 《싱가포르 자유 출판》은 싱가포르를 "마약에 찌든 동남아인들이 모인 작은 섬"이라고 묘사하였다.[46]

1867–1942년: 왕령식민지 시기

편집싱가포르는 꾸준히 성장하였지만 해협식민지 당국의 무능한 행정으로 싱가포르에 기반한 상업 커뮤니티는 영국 동인도 회사의 지배에 대한 불만이 쌓였다. 1867년 4월 1일 영국은 해협식민지를 동인도 회사가 지배하는 인도 제국에서 분리하여 국왕 직할의 왕령식민지에 편입하였다. 왕령식민지는 런던의 영국 식민성이 직접 관할하였다. 왕령식민지라 하더라도 대부분의 식민지에 대한 통치는 동인도 회사 등에 대해 위임하는 것이 일반적인 경우였지만 싱가포르에서 보인 동인도 회사의 무능으로 인해 이루어진 이 번 조치는 싱가포르의 경우 현지의 식민지 행정위원회와 해협식민지 입법위원회에 의해 행정기관이 작동하도록 하였다.[47] 각 위원회의 위원은 임명직이긴 하였으나 영국은 해가 지날수록 위원으로 뽑히는 사람 가운데 현지인을 늘려 불만을 잠재우고자 하였다.

새롭게 정비된 식민지 정부는 당면한 몇 가지 주요 문제를 해결하고자 하였다. 1877년 중국인 관리 담당이었던 윌리엄 피커링은 화교 사회에 대해 쿨리를 노예처럼 사고 파는 행위와 여성에 대한 매춘 강요를 금지한다고 선포하였다.[47] 1889년 싱가포르 지사 세실 클러먼티 스미스는 폭력 조직을 추방하였다. 이후 조직 폭력단은 공공연한 활동을 하지 못하고 지하로 숨어들었다.[47] 이러한 조치에도 불구하고 싱가포르 사회의 고질적 문제는 여전하였는데 특히 보건 문제와 주택 부족 문제는 전후 시대까지 심각한 사회 문제로 남았다. 싱가포르의 범죄 조직 역시 지하로 숨어들었을 뿐 활동이 중단된 것은 아니었다. 이들은 오히려 홍콩과 동남아시아 화교 사회에 퍼져 있던 조직 폭력단들과 연계하여 국제적인 범죄 조직망인 삼합회의 일원이 되었다. 싱가포르 삼합회 조직인 훗날 네덜란드에 거점을 마련하고 아콩으로 악명을 얻었다.[48]

중국인이 과반인 싱가포르의 상황은 정치 영역에서도 중국의 영향을 받았다. 쑨원이 청나라 타도를 위해 결성한 중국동맹회는 1906년 싱가포르 지부를 창설하였다. 중국동맹회 싱가포르 지부는 이후 동남아시아의 거점이 되었다.[47] 중국동맹회는 결국 신해혁명을 통해 중화민국을 세우는 데 일조한다.

제1차 세계대전은 싱가포르에 별다른 영향을 주지 않았다. 당시 전장은 주로 유럽과 대서양 지역이었기 때문에 동남아시아는 전쟁의 영향을 비켜갈 수 있었다. 1차 대전과 관련하여 싱가포르에서 일어난 사건은 영국이 치안 유지를 위해 고용한 세포이들이 오히려 전쟁을 틈타 영국에 반기를 든 1915년 싱가포르 반란이 유일한 군사적 충돌이었다.[49] 이 반란은 영국이 무슬림이 대부분이던 세포이를 오스만 제국과 싸우도록 출병을 명령한 것 때문에 일어났다. 세포이의 입장에서 이러한 영국 제국의 명령은 동족 상잔을 부추기는 일이었기 때문이다.[50]

1차 대전 후 영국은 커져가는 일본 제국을 견제하기 위해 싱가포르 군항을 설치하기 위한 자원을 집중하였다. 5억 달러의 비용이 들어간 군항은 1939년 완공되었으며 당시 세계 최대의 건선거와 3위의 부선거를 갖추었다. 싱가포르 군항은 영국 해군의 반년 치 보급 물자를 비축하였다. 또한 군항 수비를 위해 15 인치 해안포를 설치하고 텡아흐 공군 기지를 건설하여 영국 왕립공군 전투비행단를 배치하였다. 윈스턴 처칠은 싱가포르 군항의 지정학적 가치를 "동방의 지브롤터"라고 표현하였다. 그러나 싱가포르 군항은 이곳을 기항으로 삼는 함대가 없었다. 대신 본국의 연안 함대를 필요할 경우 수에즈를 경유하여 싱가포르에 파견하는 것이 영국 해군의 전략이었다. 그러나 막상 1939년 제2차 세계대전이 일어나자 영국 연안 함대는 모두 영국 본토 항공전에 발이 묶여 영국을 벗어날 수 없었다.[51]

1942–1945년: 일본 점령기

편집In December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the east coast of Malaya, causing the Pacific War to begin in earnest. Both attacks occurred at the same time, but due to the international dateline, the Honolulu attack is dated 7 December while the Kota Bharu attack is dated 8 December. One of Japan's objectives was to capture Southeast Asia and secure the rich supply of natural resources to feed its military and industry needs. Singapore, the main Allied base in the region, was an obvious military target because of its flourishing trade and wealth.

The British military commanders in Singapore had believed that the Japanese attack would come by sea from the south since the dense Malayan jungle in the north would serve as a natural barrier against invasion. Although they had drawn up a plan for dealing with an attack on northern Malaya, preparations were never completed. The military was confident that "Fortress Singapore" would withstand any Japanese attack and this confidence was further reinforced by the arrival of Force Z, a squadron of British warships dispatched to the defense of Singapore, including the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, and cruiser HMS Repulse. The squadron was to have been accompanied by a third capital ship, the aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable, but it ran aground en route, leaving the squadron without air cover.

On 8 December 1941, Japanese forces landed at Kota Bharu in northern Malaya. Just two days after the start of the invasion of Malaya, Prince of Wales and Repulse were sunk 50 miles off the coast of Kuantan in Pahang, by a force of Japanese bombers and torpedo bomber aircraft, in the worst British naval defeat of World War II. Allied air support did not arrive in time to protect the two capital ships.[52] After this incident, Singapore and Malaya suffered daily air raids, including those targeting civilian structures such as hospitals or shop houses with casualties ranging from the tens to the hundreds each time.

The Japanese army advanced swiftly southward through the Malay Peninsula, crushing or bypassing Allied resistance.[53] The Allied forces did not have tanks, which they considered unsuitable in the tropical rainforest, and their infantry proved powerless against the Japanese light tanks. As their resistance failed against the Japanese advance, the Allied forces were forced to retreat southwards towards Singapore. By 31 January 1942, a mere 55 days after the start of the invasion, the Japanese had conquered the entire Malay Peninsula and were poised to attack Singapore.[54]

The causeway linking Johor and Singapore was blown up by the Allied forces in an effort to stop the Japanese army. However, the Japanese managed to cross the Straits of Johor in inflatable boats days after. Several fights by the Allied forces and volunteers of Singapore's population against the advancing Japanese, such as the Battle of Pasir Panjang, took place during this period.[55] However, with most of the defenses shattered and supplies exhausted, Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival surrendered the Allied forces in Singapore to General Tomoyuki Yamashita of the Imperial Japanese Army on Chinese New Year, 15 February 1942. About 130,000 Indian, Australian, and British troops became prisoners of war, many of whom would later be transported to Burma, Japan, Korea, or Manchuria for use as slave labour via prisoner transports known as "hell ships." The fall of Singapore was the largest surrender of British-led forces in history.[56] Japanese newspapers triumphantly declared the victory as deciding the general situation of the war.[57]

Singapore, renamed Syonan-to (昭南島 Shōnan-tō, "Bright Southern Island" in Japanese), was occupied by the Japanese from 1942 to 1945. The Japanese army imposed harsh measures against the local population, with troops, especially the Kempeitai or Japanese military police, who were particularly ruthless in dealing with the Chinese population.[58] The most notable atrocity was the Sook Ching massacre of Chinese and Peranakan civilians, undertaken in retaliation against the support of the war effort in China. The Japanese screened citizens (including children) to check if they were "anti-Japanese". If so, the "guilty" citizens would be sent away in a truck to be executed. These mass executions claimed between 25,000 and 50,000 lives in Malaya and Singapore. The Japanese also launched massive purges against the Indian community, they secretly killed about 150,000 Tamil Indians and tens of thousands of Malayalam from Malaya, Burma, and Singapore in various places located near the Siam Railway.[59] The rest of the population suffered severe hardship throughout the three and a half years of Japanese occupation.[60] The Malay and Indians were forced to build the "Death Railway", a railway between Thailand and Burma (Myanmar). Most of them died while building the railway. The Eurasians[모호한 표현] were also caught as POWs (Prisoners of War).

1945–1955: Post-war period

편집After the Japanese surrender to the Allies on 15 August 1945, Singapore fell into a brief state of violence and disorder; looting and revenge-killing were widespread. British troops led by Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander for Southeast Asia Command, returned to Singapore to receive the formal surrender of the Japanese forces in the region from General Itagaki Seishiro on behalf of General Hisaichi Terauchi on 12 September 1945, and a British Military Administration was formed to govern the island until March 1946. Much of the infrastructure had been destroyed during the war, including electricity and water supply systems, telephone services, as well as the harbor facilities at the Port of Singapore. There was also a shortage of food, leading to malnutrition, disease, and rampant crime and violence. High food prices, unemployment and workers' discontent culminated in a series of strikes in 1947 causing massive stoppages in public transport and other services. By late 1947, the economy began to recover, facilitated by a growing demand for tin and rubber around the world, but it would take several more years before the economy returned to pre-war levels.[61]

The failure of Britain to defend Singapore had destroyed its credibility as an infallible ruler in the eyes of Singaporeans. The decades after the war saw a political awakening amongst the local populace and the rise of anti-colonial and nationalist sentiments, epitomised by the slogan Merdeka, or "independence" in the Malay language. The British, on their part, were prepared to gradually increase self-governance for Singapore and Malaya.[61] On 1 April 1946, the Straits Settlements was dissolved and Singapore became a separate Crown Colony with a civil administration headed by a Governor. In July 1947, separate Executive and Legislative Councils were established and the election of six members of the Legislative Council was scheduled for the following year.[62]

1948–1951: First Legislative Council

편집The first Singaporean elections, held in March 1948, were limited as only six of the twenty-five seats on the Legislative Council were to be elected. Only British subjects had the right to vote, and only 23,000 or about 10% of those eligible registered to vote. Other members of the council were chosen either by the Governor or by the chambers of commerce.[61] Three of the elected seats were won by a newly formed Singapore Progressive Party (SPP), a conservative party whose leaders were businessmen and professionals and were disinclined to press for immediate self-rule. The other three seats were won by independents.

Three months after the elections, an armed insurgency by communist groups in Malaya – the Malayan Emergency – broke out. The British imposed tough measures to control left-wing groups in both Singapore and Malaya and introduced the controversial Internal Security Act, which allowed indefinite detention without trial for persons suspected of being "threats to security". Since the left-wing groups were the strongest critics of the colonial system, progress on self-government was stalled for several years.[61]

1951–1955: Second Legislative Council

편집A second Legislative Council election was held in 1951 with the number of elected seats increased to nine. This election was again dominated by the SPP which won six seats. While this contributed to the formation of a distinct local government of Singapore, the colonial administration was still dominant. In 1953, with the communists in Malaya suppressed and the worst of the Emergency over, a British Commission, headed by Sir George Rendel, proposed a limited form of self-government for Singapore. A new Legislative Assembly with twenty-five out of thirty-two seats chosen by popular election would replace the Legislative Council, from which a Chief Minister as head of government and Council of Ministers as a cabinet would be picked under a parliamentary system. The British would retain control over areas such as internal security and foreign affairs, as well as veto power over legislation.

The election for the Legislative Assembly held on 2 April 1955 was a closely fought affair, with several new political parties joining the fray. Unlike previous elections, voters were automatically registered, expanding the electorate to around 300,000. The SPP was soundly defeated in the election, winning only four seats. The newly formed, left-leaning Labour Front was the biggest winner with ten seats and it formed a coalition government with the UMNO-MCA Alliance, which won three seats.[61] Another new party, the People's Action Party (PAP), won three seats.

1953–1954 The Fajar trial

편집Fajar trial was the first sedition trial in post-war Malaysia and Singapore. The Fajar was the publication of the University Socialist Club which mainly at that time circulated in the university campus. In May 1954, the members of the Fajar editorial board were arrested for publishing an allegedly seditious article named "Aggression in Asia". However, after three days of the trial, Fajar members were immediately released. The famous English Queen's Counsel D.N. Pritt acted as the lead counsel in the case and Lee Kuan Yew who was at that time a young lawyer-assisted him as the junior counsel. The club's final victory stands out as one of the notable landmarks in the progress of decolonisation of this part of the world.[63]

1955–1963: Self-government

편집1955–1959: Partial internal self-government

편집David Marshall, leader of the Labour Front, became the first Chief Minister of Singapore. He presided over a shaky government, receiving little cooperation from both the colonial government and the other local parties. Social unrest was on the rise, and in May 1955, the Hock Lee bus riots broke out, killing four people and seriously discrediting Marshall's government.[64] In 1956, the Chinese middle school riots broke out among students in The Chinese High School and other schools, further increasing the tension between the local government and the Chinese students and unionists who were regarded of having communist sympathies.

In April 1956, Marshall led a delegation to London to negotiate for complete self-rule in the Merdeka Talks, but the talks failed when the British were reluctant to give up control over Singapore's internal security. The British were concerned about communist influence and labour strikes which were undermining Singapore's economic stability, and felt that the local government was ineffective in handling earlier riots. Marshall resigned following the failure of the talk.

The new Chief Minister, Lim Yew Hock, launched a crackdown on communist and leftist groups, imprisoning many trade union leaders and several pro-communist members of the PAP under the Internal Security Act.[65] The British government approved of Lim's tough stance against communist agitators, and when a new round of talks was held beginning in March 1957, they agreed to grant complete internal self-government. The State of Singapore would be created, with its own citizenship. The Legislative Assembly would be expanded to fifty-one members, entirely chosen by popular election, and the Prime Minister and cabinet would control all aspects of government except defense and foreign affairs. The governorship was replaced by a Yang di-Pertuan Negara or head of state. In August 1958, the State of Singapore Act was passed in the United Kingdom Parliament providing for the establishment of the State of Singapore.[65]

1959–1963: Full internal self-government

편집Elections for the new Legislative Assembly were held in May 1959. The People's Action Party (PAP) won the polls in a landslide victory, winning forty-three of the fifty-one seats. They accomplished this by courting the Chinese-speaking majority, particularly those in the labour unions and radical student organizations. Its leader Lee Kuan Yew, a young Cambridge-educated lawyer, became the first Prime Minister of Singapore.

The PAP's victory was at first viewed with dismay by foreign and local business leaders because some party members were pro-communists. Many businesses promptly shifted their headquarters from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur.[65] Despite these ill omens, the PAP government embarked on a vigorous program to address Singapore's various economic and social problems. Economic development was overseen by the new Minister of Finance Goh Keng Swee, whose strategy was to encourage foreign and local investment with measures ranging from tax incentives to the establishment of a large industrial estate in Jurong.[65] The education system was revamped to train a skilled workforce and the English language was promoted over the Chinese language as the language of instruction. To eliminate labour unrest, existing labour unions were consolidated, sometimes forcibly, into a single umbrella organisation, called the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) with strong oversight from the government. On the social front, an aggressive and well-funded public housing program was launched to solve the long-standing housing problem. More than 25,000 high-rises, low-cost apartments were constructed during the first two years of the program.[65]

Campaign for merger

편집Despite their successes in governing Singapore, the PAP leaders, including Lee and Goh, believed that Singapore's future lay with Malaya. They felt that the historic and economic ties between Singapore and Malaya were too strong for them to continue as separate nations. Furthermore, Singapore lacked natural resources and faced both a declining entrepôt trade and a growing population that required jobs. It was thought that the merger would benefit the economy by creating a common market, eliminating trade tariffs, and thus supporting new industries which would solve the ongoing unemployment woes.

Although the PAP leadership campaigned vigorously for a merger, the sizable pro-communist wing of the PAP was strongly opposed to the merger, fearing a loss of influence as the ruling party of Malaya, United Malays National Organisation, was staunchly anti-communist and would support the non-communist faction of PAP against them. The UMNO leaders were also skeptical of the idea of a merger due to their distrust of the PAP government and concerns that the large Chinese population in Singapore would alter the racial balance on which their political power base depended. The issue came to a head in 1961 when pro-communist PAP minister Ong Eng Guan defected from the party and beat a PAP candidate in a subsequent by-election, a move that threatened to bring down Lee's government.

Faced with the prospect of a takeover by the pro-communists, UMNO changed their minds about the merger. On 27 May, Malaya's Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, mooted the idea of a Federation of Malaysia, comprising existing Federation of Malaya, Singapore, Brunei and the British Borneo territories of North Borneo and Sarawak. The UMNO leaders believed that the additional Malay population in the Borneo territories would offset Singapore's Chinese population.[65] The British government, for its part, believed that the merger would prevent Singapore from becoming a haven for communism. Lee called for a referendum on the merger, to be held in September 1962, and initiated a vigorous campaign in advocation of their proposal of merger, possibly aided by the fact that the government had a large influence over the media.

The referendum did not have an option of objecting to the idea of merger because no one had raised the issue in the Legislative Assembly before then. However, the method of merger had been debated, by the PAP, Singapore People's Alliance and the Barisian Sosialis, each with their own proposals. The referendum was called therefore, was to resolve this issue.

The referendum called had three options. Singapore could join Malaysia, but would be granted full autonomy and only with fulfilment of conditions to guarantee that, which was option A. The second option, option B, called for full integration into Malaysia without such autonomy, with the status of any other state in Malaysia. The third option, option C, was to enter Malaysia "on terms no less favourable than the Borneo territories", noting the motive of why Malaysia proposed the Borneo territories to join as well. After the referendum was held, the option A received 70% of the votes in the referendum, with 26% of the ballots left blank as advocated by the Barisan Sosialis to protest against option A. The other two plans received less than two percent each.

On 9 July 1963, the leaders of Singapore, Malaya, Sabah and Sarawak signed the Malaysia Agreement to establish the Malaysia which was planned to come into being on 31 August. Nonetheless, on 31 August 1963 (the original Malaysia Day), Lee Kuan Yew stood in front of a crowd at the Padang in Singapore and unilaterally declared Singapore's independence. On the 31 of August, Singapore declared its independence from the United Kingdom, with Yusof bin Ishak as the head of state (Yang di-Pertuan Negara) and Lee Kuan Yew as prime minister. However it was postponed by Tunku Abdul Rahman to 16 September 1963, to accommodate a United Nations mission to North Borneo and Sarawak to ensure that they really wanted a merger, which was prompted by Indonesian objections to the formation of Malaysia. On 16 September 1963, coincidentally Lee's fortieth birthday, he once again stood in front of a crowd at the Padang and this time proclaimed Singapore as part of Malaysia. Pledging his loyalty to the Central Government, the Tunku and his colleagues, Lee asked for ‘an honourable relationship between the states and the Central Government, a relationship between brothers, and not a relationship between masters and servants

1963–1965: Singapore in Malaysia

편집Merger

편집On 16 September 1963, Malaya, Singapore, North Borneo and Sarawak were merged and Malaysia was formed.[65] The union was rocky from the start. During the 1963 Singapore state elections, a local branch of United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) took part in the election despite an earlier UMNO's agreement with the PAP not to participate in the state's politics during Malaysia's formative years. Although UMNO lost all its bids, relations between PAP and UMNO worsened. The PAP, in a tit-for-tat, challenged UMNO candidates in the 1964 federal election as part of the Malaysian Solidarity Convention, winning one seat in the Malaysian Parliament.

Racial tension

편집Racial tensions increased as ethnic Chinese and other non-Malay ethnic groups in Singapore rejected the discriminatory policies imposed by the Malays such as quotas for the Malays as special privileges were granted to the Malays guaranteed under Article 153 of the Constitution of Malaysia. There were also other financial and economic benefits that were preferentially given to Malays. Lee Kuan Yew and other political leaders began advocating for the fair and equal treatment of all races in Malaysia, with a rallying cry of "Malaysian Malaysia!".

Meanwhile, the Malays in Singapore were being increasingly incited by the federal government's accusations that the PAP was mistreating the Malays. The external political situation was also tense; Indonesian President Sukarno declared a state of Konfrontasi (Confrontation) against Malaysia and initiated military and other actions against the new nation, including the bombing of MacDonald House in Singapore 10 March 1965 by Indonesian commandos, killing three people.[66] Indonesia also conducted sedition activities to provoke the Malays against the Chinese.[65] The most notorious riots were the 1964 Race Riots that first took place on Prophet Muhammad's birthday on 21 July with twenty-three people killed and hundreds injured, and also, many people by then still hated the rest. During the unrest, the price of food skyrocketed when the transport system was disrupted, causing further hardship for the people.

The state and federal governments also had conflicts on the economic front. UMNO leaders feared that the economic dominance of Singapore would inevitably shift political power away from Kuala Lumpur. Despite earlier agreement to establish a common market, Singapore continued to face restrictions when trading with the rest of Malaysia. In retaliation, Singapore refused to provide Sabah and Sarawak the full extent of the loans previously agreed to for the economic development of the two eastern states.[출처 필요] The Bank of China branch of Singapore was closed by the Central Government in Kuala Lumpur as it was suspected of funding communists. The situation escalated to such an extent that talks between UMNO and the PAP broke down, and abusive speeches and writings became rife on both sides. UMNO extremists called for the arrest of Lee Kuan Yew.

Separation

편집Seeing no alternative to avoid further bloodshed, the Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman decided to expel Singapore from the federation. Goh Keng Swee, who had become skeptical of the merger's economic benefits for Singapore, convinced Lee Kuan Yew that the separation had to take place. UMNO and PAP representatives worked out the terms of separation in extreme secrecy in order to present the British government, in particular, with a fait accompli.

On 9 August 1965, the Parliament of Malaysia voted 126–0 in favor of a constitutional amendment expelling Singapore from the federation. A tearful Lee Kuan Yew announced in a televised press conference that Singapore had become a sovereign, independent nation. In a widely remembered quote, he stated: "For me, it is a moment of anguish. All my life, my whole adult life, I have believed in merger and unity of the two territories."[67][68] The new state became the Republic of Singapore, with Yusof bin Ishak appointed as its first President.[69]

1965–present: Republic of Singapore

편집1965 to 1979

편집After gaining independence abruptly, Singapore faced a future filled with uncertainties. The Konfrontasi was on-going and the conservative UMNO faction strongly opposed the separation; Singapore faced the dangers of attack by the Indonesian military and forcible re-integration into the Malaysia Federation on unfavorable terms. Much of the international media was skeptical of prospects for Singapore's survival. Besides the issue of sovereignty, the pressing problems were unemployment, housing, education, and the lack of natural resources and land.[70] Unemployment was ranging between 10 and 12%, threatening to trigger civil unrest.

Singapore immediately sought international recognition of its sovereignty. The new state joined the United Nations on 21 September 1965, becoming the 117th member; and joined the Commonwealth in October that year. Foreign minister Sinnathamby Rajaratnam headed a new foreign service that helped assert Singapore's independence and establishing diplomatic relations with other countries.[71] On 22 December 1965, the Constitution Amendment Act was passed under which the Head of State became the President and the State of Singapore became the Republic of Singapore. Singapore later co-founded the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on 8 August 1967 and was admitted into the Non-Aligned Movement in 1970.[72]

The Economic Development Board had been set up in 1961 to formulate and implement national economic strategies, focusing on promoting Singapore's manufacturing sector.[73] Industrial estates were set up, especially in Jurong, and foreign investment was attracted to the country with tax incentives. The industrialization transformed the manufacturing sector to one that produced higher value-added goods and achieved greater revenue. The service industry also grew at this time, driven by demand for services by ships calling at the port and increasing commerce. This progress helped to alleviate the unemployment crisis. Singapore also attracted big oil companies like Shell and Esso to establish oil refineries in Singapore which, by the mid-1970s, became the third-largest oil-refining centre in the world.[70] The government invested heavily in an education system that adopted English as the language of instruction and emphasised practical training to develop a competent workforce well suited for the industry.

The lack of good public housing, poor sanitation, and high unemployment led to social problems from crime to health issues. The proliferation of squatter settlements resulted in safety hazards and caused the Bukit Ho Swee Fire in 1961 that killed four people and left 16,000 others homeless.[74] The Housing Development Board set up before independence continued to be largely successful and huge building projects sprung up to provide affordable public housing to resettle the squatters. Within a decade, the majority of the population had been housed in these apartments. The Central Provident Fund (CPF) Housing Scheme, introduced in 1968, allows residents to use their compulsory savings account to purchase HDB flats and gradually increases home-ownership in Singapore.[75]

British troops had remained in Singapore following its independence, but in 1968, London announced its decision to withdraw the forces by 1971.[76] With the secret aid of military advisers from Israel, Singapore rapidly established the Singapore Armed Forces, with the help of a national service program introduced in 1967.[77] Since independence, Singaporean defense spending has been approximately five percent of GDP.[출처 필요]

The 1980s and 1990s

편집Further economic success continued through the 1980s, with the unemployment rate falling to 3% and real GDP growth averaging at about 8% up until 1999. During the 1980s, Singapore began to upgrade to higher-technological industries, such as the wafer fabrication sector, in order to compete with its neighbours which now had cheaper labour. Singapore Changi Airport was opened in 1981 and Singapore Airlines was developed to become a major airline.[78] The Port of Singapore became one of the world's busiest ports and the service and tourism industries also grew immensely during this period. Singapore emerged as an important transportation hub and a major tourist destination.[79]

The Housing Development Board (HDB) continued to promote public housing with new towns, such as Ang Mo Kio, being designed and built. These new residential estates have larger and higher-standard apartments and are served with better amenities. Today, 80–90% of the population lives in HDB apartments. In 1987, the first Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) line began operation, connecting most of these housing estates and the city centre.[80]

The political situation in Singapore continues to be dominated by the People's Action Party. The PAP won all the parliamentary seats in every election between 1966 and 1981.[81] The PAP rule is termed authoritarian by some activists and opposition politicians who see the strict regulation of political and media activities by the government as an infringement on political rights.[82] The conviction of opposition politician Chee Soon Juan for illegal protests and the defamation lawsuits against J.B. Jeyaretnam have been cited by the opposition parties as examples of such authoritarianism.[83] The lack of separation of powers between the court system and the government led to further accusations by the opposition parties of miscarriage of justice.[출처 필요]

The government of Singapore underwent several significant changes. Non-Constituency Members of Parliament were introduced in 1984 to allow up to three losing candidates from opposition parties to be appointed as MPs. Group Representation Constituencies (GRCs) was introduced in 1988 to create multi-seat electoral divisions, intended to ensure minority representation in parliament.[84] Nominated Members of Parliament were introduced in 1990 to allow non-elected non-partisan MPs.[85] The Constitution was amended in 1991 to provide for an Elected President who has veto power in the use of national reserves and appointments to public office.[86] The opposition parties have complained that the GRC system has made it difficult for them to gain a foothold in parliamentary elections in Singapore, and the plurality voting system tends to exclude minority parties.[87]

In 1990, Lee Kuan Yew passed the reins of leadership to Goh Chok Tong, who became the second prime minister of Singapore. Goh presented a more open and consultative style of leadership as the country continued to modernise. In 1997, Singapore experienced the effect of the Asian financial crisis and tough measures, such as cuts in the CPF contribution, were implemented.[출처 필요]

Lee's programs in Singapore had a profound effect on the Communist leadership in China, who made a major effort, especially under Deng Xiaoping, to emulate his policies of economic growth, entrepreneurship, and subtle suppression of dissent. Over 22,000 Chinese officials were sent to Singapore to study its methods.[88]

2000–present

편집Early 2000s

편집Singapore went through some of its most serious postwar crises in the early 21st century, including the SARS outbreak in 2003 and the rising threat of terrorism. In December 2001, a plot to bomb embassies and other infrastructure in Singapore was uncovered[89] and as many as 36 members of the Jemaah Islamiyah group were arrested under the Internal Security Act.[90] Major counter-terrorism measures were put in place to detect and prevent potential terrorist acts and to minimise damages should they occur.[91] More emphasis was placed on promoting social integration and trust between the different communities.[92] There are also increasing reforms in the Education system. Primary education was made compulsory in 2003.[93]

In 2004, then Deputy Prime Minister of Singapore Lee Hsien Loong, the eldest son of Lee Kuan Yew, took over from incumbent Goh Chok Tong and became the third prime minister of Singapore. He introduced several policy changes, including the reduction of national service duration from two and a half years to two years, and the legalisation of casino gambling.[94] Other efforts to raise the city's global profile included the reestablishment of the Singapore Grand Prix in 2008, and the hosting of the 2010 Summer Youth Olympics.

The general election of 2006 was a landmark election because of the prominent use of the internet and blogging to cover and comment on the election, circumventing the official media.[95] The PAP returned to power, winning 82 of the 84 parliamentary seats and 66% of the votes.[96]

On 3 June 2009, Singapore commemorated 50 years of self-governance.

2010s

편집Singapore's move to increase attractiveness as a tourist destination was further boosted in March 2010 with the opening of Universal Studios Singapore at Resorts World Sentosa.[97] In the same year, Marina Bay Sands Integrated Resorts was also opened. Marina Bay Sands was billed as the world's most expensive standalone casino property at S$8 billion.[98] On 31 December 2010, it was announced that Singapore's economy grew by 14.7% for the whole year, the best growth on record ever for the country.[99]

The general election of 2011 was yet another watershed election as it was the first time a Group Representation Constituency (GRC) was lost by the ruling party PAP, to the opposition Workers' Party.[100] The final results saw a 6.46% swing against the PAP from the 2006 elections to 60.14%, its lowest since independence.[101] Nevertheless, PAP won 81 out of 87 seats and maintained its parliamentary majority.

Lee Kuan Yew, founding father and the first Prime Minister of Singapore, died on 23 March 2015. Singapore declared a period of national mourning from 23 to 29 March.[102] Lee Kuan Yew was accorded a state funeral.

The year 2015 also saw Singapore celebrate its Golden Jubilee of 50 years of independence. An extra day of the holiday, 7 August 2015, was declared to celebrate Singapore's Golden Jubilee. Fun packs, which are usually given to people who attend the National Day Parade were given to every Singaporean and PR household. In commemoration of the significant milestone, the 2015 National Day Parade was the first-ever parade to be held both at the Padang and the Float at Marina Bay. NDP 2015 was the first National Day Parade without the founding leader Lee Kuan Yew, who never missed a single National Day Parade since 1966.

The 2015 General Elections was held on 11 September shortly after the 2015 National Day Parade. The election was the first since Singapore's independence which saw all seats contested.[103] The election was also the first after the death of Lee Kuan Yew (the nation's first Prime Minister and an MP until his passing). The ruling party PAP received its best results since 2001 with 69.86% of the popular vote, an increase of 9.72% from the previous election in 2011.[104]

Following amendments to the Constitution of Singapore, Singapore held its first reserved Presidential Elections in 2017. The election was the first to be reserved for a particular racial group under a hiatus-triggered model. The 2017 election was reserved for candidates from the minority Malay community. Then Speaker of Parliament Halimah Yacob won the elections though a walkover and was inaugurated as the eighth President of Singapore on 14 September 2017, becoming the first female President of Singapore.

See also

편집- History of Southeast Asia

- History of East Asia

- List of years in Singapore

- List of Prime Ministers of Singapore

- Military history of Singapore

- Timeline of Singaporean history

- The Little Nyonya

- Together (Singaporean TV series)

- List of The Journey episodes

- The Journey (trilogy series)

- The Journey: A Voyage

- The Journey: Tumultuous Times

- The Journey: Our Homeland

References

편집- ↑ “GDP per capita (current US$) - Singapore, East Asia & Pacific, Japan, Korea”. 《World Bank》.

- ↑ “Report for Selected Countries and Subjects”. 《www.imf.org》. 2019년 10월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Report for Selected Countries and Subjects”. 《www.imf.org》. 2019년 10월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ “GDP per capita (current US$) - Singapore, East Asia & Pacific, Japan, Korea”. 《World Bank》.

- ↑ Hack, Karl. “Records of Ancient Links between India and Singapore”. National Institute of Education, Singapore. 2006년 4월 26일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 8월 4일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 “Singapore: History, Singapore 1994”. Asian Studies @ University of Texas at Austin. 2007년 3월 23일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella, 편집. 《The Indianized States of Southeast Asia》. trans. Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. 142–143쪽. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ↑ Epigraphia Carnatica, Volume 10, Part 1, page 41

- ↑ Sar Desai, D. R. (2012년 12월 4일). 《Southeast Asia: Past and Present》. 43쪽. ISBN 9780813348384.

- ↑ 島夷誌略

- ↑ “Sri Vijaya-Malayu: Singapore and Sumatran Kingdoms”. 《History SG》.

- ↑ Victor R Savage, Brenda Yeoh (2013). 《Singapore Street Names: A Study of Toponymics》. Marshall Cavendish. 381쪽. ISBN 978-9814484749.

- ↑ 가 나 C.M. Turnbull (2009). 《A History of Modern Singapore, 1819–2005》. NUS Press. 21–22쪽. ISBN 978-9971694302.

- ↑ Community Television Foundation of South Florida (2006년 1월 10일). “Singapore: Relations with Malaysia”. Public Broadcasting Service. 2006년 12월 22일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “Archaeology in Singapore – Fort Canning Site”. Southeast-Asian Archaeology. 2007년 4월 29일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ Derek Heng Thiam Soon (2002). “Reconstructing Banzu, a Fourteenth-Century Port Settlement in Singapore”. 《Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society》. 75, No. 1 (282): 69–90.

- ↑ Paul Wheatley (1961). 《The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500》. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya. 82–85쪽. OCLC 504030596.

- ↑ “Hybrid Identities in the Fifteenth-Century Straits of Malacca” (PDF). Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. 2015년 11월 29일에 원본 문서 (PDF)에서 보존된 문서. 2017년 10월 24일에 확인함.

- ↑ John Miksic (2013). 《Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300–1800》. NUS Press. 120쪽. ISBN 978-9971695743.

- ↑ “Singapore – Precolonial Era”. U.S. Library of Congress. 2006년 6월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ John N. Miksic (2013). 《Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300_1800》. NUS Press. 155–163쪽. ISBN 978-9971695743.

- ↑ “Singapura as "Falsa Demora"”. 《Singapore SG》. National Library Board Singapore.

- ↑ Afonso de Albuquerque (2010). 《The Commentaries of the Great Afonso Dalboquerque, Second Viceroy of India》. Cambridge University Press. 73쪽. ISBN 978-1108011549.

- ↑ Borschberg, P. (2010). 《The Singapore and Melaka Straits. Violence, Security and Diplomacy in the 17th century》. Singapore: NUS Press. 157–158쪽. ISBN 978-9971694647.

- ↑ “Country Studies: Singapore: History”. U.S. Library of Congress. 2007년 5월 1일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 바 Leitch Lepoer, Barbara (1989). 《Singapore: A Country Study》. Country Studies. GPO for tus/singapore/4.htm. 2010년 2월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Saw Swee-Hock (2012년 6월 30일). 《The Population of Singapore》 3판. ISEAS Publishing. 7–8쪽. ISBN 978-9814380980.

- ↑ Lily Zubaidah Rahim, Lily Zubaidah Rahim (2010년 11월 9일). 《Singapore in the Malay World: Building and Breaching Regional Bridges》. Taylor & Francis. 24쪽. ISBN 9781134013975.

- ↑ Jenny Ng (1997년 2월 7일). “1819 – The February Documents”. Ministry of Defence. 2006년 7월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Milestones in Singapore's Legal History”. Supreme Court, Singapore. 2006년 7월 18일에 확인함.[깨진 링크]

- ↑ Lily Zubaidah Rahim, Lily Zubaidah Rahim (2010). 《Singapore in the Malay World: Building and Breaching Regional Bridges》. Taylor & Francis. 24쪽. ISBN 978-1134013975.

- ↑ “The Malays”. National Heritage Board 2011. 2011년 2월 23일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2011년 7월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 “First Census of Singapore is Taken”. 《History SG》.

- ↑ Wright, Arnold; Cartwright, H.A., 편집. (1907). 《Twentieth century impressions of British Malaya: its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources》. 37쪽.

- ↑ Brenda S.A. Yeoh (2003). 《Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment》. NUS Press. 317쪽. ISBN 978-9971692681.

- ↑ “Founding of Modern Singapore”. Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. 2009년 5월 8일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2011년 4월 13일에 확인함.

- ↑ Saw Swee-Hock (March 1969). “Population Trends in Singapore, 1819–1967”. 《Journal of Southeast Asian History》 10 (1): 36–49. doi:10.1017/S0217781100004270. JSTOR 20067730.

- ↑ C.M. Turnbull (2009). 《A History of Modern Singapore, 1819–2005》. NUS Press. 40–41쪽. ISBN 978-9971694302.

- ↑ Bastin, John. "Malayan Portraits: John Crawfurd", in Malaya, vol.3 (December 1954), pp. 697–698.

- ↑ JCM Khoo; CG Kwa; LY Khoo (1998). “The Death of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781–1826)”. Singapore Medical Journal. 2006년 9월 3일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 “Singapore – A Flourishing Free Ports”. U.S. Library of Congress. 2006년 7월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ Crossroads: A Popular History of Malaysia and Singapore (Ch. 5), Jim Baker, Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd, 2012.

- ↑ “The Straits Settlements”. Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. 2006년 7월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ George P. Landow. “Singapore Harbor from Its Founding to the Present: A Brief Chronology”. 2005년 5월 5일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ Lim, Irene. (1999) Secret societies in Singapore, National Heritage Board, Singapore History Museum, Singapore ISBN 978-9813018792

- ↑ Singapore Free Press, 21 July 1854

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 “Crown Colony”. U.S. Library of Congress. 2006년 7월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ 중국계 폭력 조직 진단 ② / 홍콩, 삼합회, 시사저널, 1996년 8월 1일

- ↑ Harper, R. W. E. & Miller, Harry (1984). Singapore Mutiny. Singapore: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195825497

- ↑ “Singapore Massacre (1915)”. National Ex-Services Association. 2005년 12월 17일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ W. David McIntyre (1979). The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919–1942 London: Macmillan, ISBN 978-0333248676

- ↑ Martin Middlebrook and Patrick Mahonehy Battleship: The Sinking of the Prince of Wales and the Repulse (Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1979)

- ↑ “The Malayan Campaign 1941”. 2005년 11월 19일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2005년 12월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ Peter Thompson (2005). The Battle for Singapore, London, ISBN 978-0749950682

- ↑ Smith, Colin (2005). Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II. Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0670913411

- ↑ John George Smyth (1971) Percival and the Tragedy of Singapore, MacDonald and Company, ASIN B0006CDC1Q

- ↑ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945 p. 277 Random House, New York 1970

- ↑ Kang, Jew Koon. "Chinese in Singapore during the Japanese occupation, 1942–1945." Academic exercise – Dept. of History, National University of Singapore, 1981.

- ↑ Kolappan, B. (2016년 8월 27일). “The real Kwai killed over 1.50 lakh Tamils”. 《The Hindu》. 2016년 9월 21일에 확인함.

- ↑ Blackburn, Kevin. "The Collective Memory of the Sook Ching Massacre and the Creation of the Civilian War Memorial of Singapore". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 73, 2 (December 2000), 71–90.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 “Singapore – Aftermath of War”. U.S. Library of Congress. 2006년 6월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Towards Self-government”. Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts, Singapore. 2006년 7월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 6월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ Poh, Soo K (2010). 《The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of Postwar Malaya and Singapore》. Petaling Jaya: SIRD. 121쪽. ISBN 978-9833782864.

- ↑ “1955– Hock Lee Bus Riots”. Singapore Press Holdings. 2006년 5월 11일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 6월 27일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 바 사 아 “Singapore – Road to Independence”. U.S. Library of Congress. 2006년 6월 27일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Terror Bomb Kills 2 Girls at Bank”. 《The Straits Times》 (Singapore). 1965년 3월 11일. 2014년 2월 1일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Transcript, Press Conference Given By Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, 9 August 1965, 21–22.

- ↑ “Road to Independence”. AsiaOne. 2013년 10월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 6월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Singapore Infomap – Independence”. Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. 2006년 7월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 17일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 “Singapore – Two Decades of Independence”. U.S. Library of Congress. 2006년 6월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Former DPM Rajaratnam dies at age 90”. Channel NewsAsia. 2006년 2월 22일. 2009년 7월 16일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “About MFA, 1970s”. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2004년 12월 10일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 17일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Singapore Infomap – Coming of Age”. Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. 2006년 7월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 17일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Milestone – 1888–1990”. Singapore Civil Defence Force. 2006년 5월 10일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 17일에 확인함.

- ↑ “History of CPF”. Central Provident Fund. 2006년 10월 4일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 17일에 확인함.

- ↑ N. Vijayan (1997년 1월 7일). “1968 – British Withdrawal”. Ministry of Defence (Singapore). 2006년 7월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ Lim Gek Hong (2002년 3월 7일). “1967 – March 1967 National Service Begins”. Ministry of Defence (Singapore). 2006년 7월 17일에 확인함.

- ↑ “History of Changi Airport”. Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore. 2006년 6월 29일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ hermes (2016년 1월 10일). “Today (1991-2016): Looking ahead to becoming an inclusive, global city”. 《The Straits Times》 (영어). 2021년 8월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ "1982 – The Year Work Began" 보관됨 5 6월 2011 - 웨이백 머신, Land Transport Authority. Retrieved 7 December 2005.

- ↑ “Parliamentary By-Election 1981”. Singapore-elections.com. 2008년 12월 4일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “Singapore elections”. BBC. 2006년 5월 5일.

- ↑ “Report 2005 – Singapore”. Amnesty International. December 2004. 2008년 6월 4일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “Parliamentary Elections Act”. Singapore Statutes Online. 2006년 5월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ Ho Khai Leong (2003). Shared Responsibilities, Unshared Power: The Politics of Policy-Making in Singapore. Eastern Univ Pr. ISBN 978-9812102188

- ↑ “Presidential Elections”. Elections Department Singapore. 2006년 4월 18일. 2008년 8월 27일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Chua Beng Huat (1995). Communitarian Ideology and Democracy in Singapore. Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0203033722

- ↑ Chris Buckley, "In Lee Kuan Yew, China Saw a Leader to Emulate," The New York Times 23 March 2015

- ↑ “white Paper – The Jemaah Islamiyah Arrests and the Threat of Terrorism”. Ministry of Home Affairs, Singapore. 2003년 1월 7일. 2008년 10월 11일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “Innocent detained as militants in Singapore under Internal Security Act – govt”. Agence France-Presse. 2005년 11월 11일.

- ↑ “Counter-Terrorism”. Singapore Police Force. 2007년 6월 12일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2006년 7월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Inter-Racial and Religious Confidence Circles”.

- ↑ “Compulsory Education”. 《www.moe.gov.sg》. 2018년 1월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ Lee Hsien Loong (2005년 4월 18일). “Ministerial Statement – Proposal to develop Integrated Resorts”. Channel NewsAsia. 2007년 9월 12일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “bloggers@elections.net”. Today (Singapore newspaper). 2006년 3월 18일. 2006년 11월 21일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “Singapore's PAP returned to power”. Channel NewsAsia. 2006년 5월 7일. 2009년 7월 16일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “Breaking News from Straits Times”. 《ussingapore.blogspot.sg》. 2018년 1월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Las Vegas Sands says Singapore casino opening delayed”. 《archive.is》. 2013년 6월 2일. 2013년 6월 2일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2018년 1월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Singapore economy in 14.7% growth”. 《BBC News》. 2011. 2018년 1월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Results”. Channel NewsAsia. 2011년 12월 28일. 2012년 3월 23일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2011년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Singapore opposition makes historic gains”. 《Financial Times》. 2018년 1월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Prime Minister declares period of National Mourning for Mr Lee Kuan Yew”. Channel NewsAsia. 2015년 3월 23일. 2015년 5월 12일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2015년 5월 30일에 확인함.

- ↑ “GE2015: Voter turnout at 93.56 per cent, improves slightly from 2011 record low, Politics News & Top Stories”. 《The Straits Times》. 2015년 9월 13일. 2015년 9월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2018년 1월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ “For PAP, the numbers hark back to 2001 polls showing, Politics News & Top Stories”. 《The Straits Times》. 2015년 9월 12일. 2015년 9월 12일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2018년 1월 3일에 확인함.

Bibliography

편집- Abshire, Jean. The history of Singapore (ABC-CLIO, 2011).

- Baker, Jim. Crossroads: a popular history of Malaysia and Singapore (Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd, 2020).

- Bose, Romen (2010). 《The End of the War : Singapore's Liberation and the Aftermath of the Second World War》. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9789814435475.

- Corfield, Justin J. Historical dictionary of Singapore (2011) online

- Guan, Kwa Chong, et al. Seven hundred years: a history of Singapore (Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd, 2019)

- Heng, Derek, and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied, eds. Singapore in global history (Amsterdam University Press, 2011) scholarly essays online

- Huang, Jianli. "Stamford Raffles and the'founding'of Singapore: The politics of commemoration and dilemmas of history." Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 91.2 (2018): 103-122 online.

- Kratoska. Paul H. The Japanese Occupation of Malaya and Singapore, 1941–45: A Social and Economic History (NUS Press, 2018). pp. 446.

- Lee, Kuan Yew. From Third World To First: The Singapore Story: 1965–2000. (2000).

- Miksic, John N. (2013). 《Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300–1800》. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-574-3.

- Perry, John Curtis. Singapore: Unlikely Power (Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Tan, Kenneth Paul (2007). 《Renaissance Singapore? Economy, Culture, and Politics》. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971693770.

- Woo, Jun Jie. Singapore as an international financial centre: History, policy and politics (Springer, 2016).

Historiography

편집- Abdullah, Walid Jumblatt. "Selective history and hegemony-making: The case of Singapore." International Political Science Review 39.4 (2018): 473–486.

- Kwa, Chong Guan, and Peter Borschberg. Studying Singapore before 1800 (NUS Press Pte Ltd, 2018).

- Lawrence, Kelvin. "Greed, guns and gore: Historicising early British colonial Singapore through recent developments in the historiography of Munsyi Abdullah." Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 50.4 (2019): 507-520.

- Seng, Loh Kah. "History, memory, and identity in modern Singapore: Testimonies from the urban margins." The Oral History Review (2019) online.

- Seng Loh, Kah. "Writing social histories of Singapore and making do with the archives." South East Asia Research (2020): 1-14.

- Seng, Loh Kah. "Black areas: urban kampongs and power relations in post-war Singapore historiography." Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 22.1 (2007): 1-29.

External links

편집| Jjw/작업장3 관련 도서관 자료 |

- Singapore History The biographical and geographical histories are of particular interest.

- A dream shattered Full text of Tunku Abdul Rahman's speech to the Parliament of Malaysia announcing separation

- iremember.sg Visual representation of memories of Singapore, in the form of pictures, stories that are geographically tagged and laid out on the Singapore map. These pictures are also tagged by when they took place, allowing you to see how Singapore has changed through time.