위키프로젝트:군사/6.25 전쟁

6.25 전쟁 또는 한국 전쟁(Korean War)는 1950년 6월 25일 북한의 남한 침공부터 시작되어 1953년 7월 27일 휴전 협정 체결까지 이어진 대한민국과 조선민주주의인민공화국 사이에서 벌어졌던 전쟁이다. 조선민주주의인민공화국은 중화인민공화국과 소련의 지원을 받았으며, 대한민국은 미국이 지도하는 유엔군사령부(UNC)의 지원을 받았다.[c]

When World War II ended, Korea, which had been a Japanese colony for 35 years, was divided by the Soviet Union and US at the 38th parallel into two occupation zones[d] with plans for an independent Korea. Due to political disagreements, each zone eventually formed its own government in 1948. The north was led by Kim Il Sung in Pyongyang, while the south by Syngman Rhee in Seoul.

Both claimed to be the sole legitimate government of all Korea and engaged in limited battles along the 38th parallel,[35][36][37] while Seoul also put down communist uprisings. North Korean troops invaded across the 38th parallel on 25 June 1950.[38][39] In the absence of the Soviet Union,[c] the United Nations Security Council denounced the attack and recommended countries to repel the North Korean army (KPA), under the United Nations Command.[41] UN forces comprised 21 countries, with the US providing around 90% of military personnel.[42][43]

After two months, the South Korean army (ROKA) and its allies were nearly defeated, holding onto only the Pusan Perimeter. In September 1950, however, UN forces landed at Inchon, cutting off KPA troops and supply lines. They invaded North Korea in October 1950 and advanced towards the Yalu River—the border with China. On 19 October 1950, the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) crossed the Yalu and entered the war.[38] UN forces retreated from North Korea following PVA's first and second offensive. Communist forces captured Seoul again in January 1951 before losing it. Following the abortive Chinese spring offensive, they were pushed back to the 38th parallel, and the final two years turned into a war of attrition.

The combat ended on 27 July 1953 when the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed, allowing the exchange of prisoners and the creation of the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The conflict displaced millions of people, inflicting 3 million fatalities and a larger proportion of civilian deaths than World War II or the Vietnam War. Alleged war crimes include the killing of suspected communists by Seoul and the torture and starvation of prisoners of war by the North Koreans.[출처 필요] North Korea became one of the most heavily bombed countries in history.[44] Virtually all of Korea's major cities were destroyed.[45] No peace treaty was ever signed, making this a frozen conflict.[46][47]

명칭

편집| Korean War | |||||||

| 문화어 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 조선글 | 조국해방전쟁 | ||||||

| 한자 | 祖國解放戰爭 | ||||||

| |||||||

| 표준어 | |||||||

| 한글 | 6·25 전쟁 or 한국 전쟁 | ||||||

| 한자 | 六二五戰爭 or 韓國戰爭 | ||||||

| |||||||

In South Korea, the war is usually referred to as the "625 War" (틀:Korean), the "625 Upheaval" (틀:Korean), or simply "625", reflecting the date of its commencement on 25 June.[48]

In North Korea, the war is officially referred to as the Fatherland Liberation War (Choguk haebang chŏnjaeng) or alternatively the "Chosŏn [Korean] War" (틀:Korean).[49]

In mainland China, the segment of the war after the intervention of the People's Volunteer Army is commonly and officially known as the "Resisting America and Assisting Korea War"[50] (중국어 정체자: 抗美援朝战争, 병음: Kàngměi Yuáncháo Zhànzhēng), although the term "Chosŏn War" (중국어 정체자: 朝鮮戰爭, 병음: Cháoxiǎn Zhànzhēng) is sometimes used unofficially. The term "Hán (Korean) War" (중국어 정체자: 韓戰, 병음: Hán Zhàn) is most used in Taiwan (Republic of China), Hong Kong and Macau.

In the US, the war was initially described by President Harry S. Truman as a "police action", as the US never formally declared war on its opponents, and the operation was conducted under the auspices of the UN.[51] It has been sometimes referred to in the English-speaking world as "The Forgotten War" or "The Unknown War" because of the lack of public attention it received during and afterwards, relative to the global scale of World War II, which preceded it, and the subsequent angst of the Vietnam War, which succeeded it.[52][53]

배경

편집일제강점기

편집Imperial Japan diminished the influence of China over Korea in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), ushering in the short-lived Korean Empire.[54] A decade later, after defeating Imperial Russia in the Russo-Japanese War, Japan made the Korean Empire its protectorate with the Eulsa Treaty in 1905, then annexed it with the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910. The Korean Empire fell, and Korea was directly ruled by Japan between 1910-45.[55]

Many Korean nationalists fled the country. The Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea was founded in 1919 in Nationalist China. It failed to achieve international recognition, failed to unite the nationalist groups, and had a fractious relationship with its US-based founding president, Syngman Rhee.[56] From 1919 to 1925 and beyond, Korean communists led internal and external warfare against the Japanese.[57][58]

In China, the nationalist National Revolutionary Army and the communist People's Liberation Army (PLA) helped organize Korean refugees against the Japanese military, which had also occupied parts of China. The Nationalist-backed Koreans, led by Yi Pom-Sok, fought in the Burma campaign (1941-45). The communists, led by, among others, Kim Il Sung, fought the Japanese in Korea and Manchuria.[59] At the Cairo Conference in 1943, China, the UK and the US decided that "in due course Korea shall become free and independent".[60]

한반도 분단

편집At the Tehran Conference in 1943 and the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the Soviet Union promised to join its allies in the Pacific War within three months of the victory in Europe. Germany officially surrendered on 8 May 1945, and the USSR declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria on 8 August 1945, three days after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.[58][61] By 10 August, the Red Army had begun to occupy the north of Korea.[62]

On 10 August in Washington, US Colonels Dean Rusk and Charles H. Bonesteel III were assigned to divide Korea into Soviet and US occupation zones and proposed the 38th parallel as the dividing line. This was incorporated into the US General Order No. 1, which responded to the Japanese surrender on 15 August. Explaining the choice of the 38th parallel, Rusk observed, "even though it was further north than could be realistically reached by U. S. [sic] forces in the event of Soviet disagreement ... we felt it important to include the capital of Korea in the area of responsibility of American troops". He noted that he was "faced with the scarcity of U.S. forces immediately available and time and space factors which would make it difficult to reach very far north before Soviet troops could enter the area".[63][64] As Rusk's comments indicate, the US doubted whether the Soviets would agree to this.[65][66][67][68] Joseph Stalin, however, maintained his wartime policy of co-operation, and on 16 August the Red Army halted at the 38th parallel for three weeks to await the arrival of US forces.[62]

On 7 September 1945, General Douglas MacArthur issued Proclamation No. 1 to the people of Korea, announcing US military control over Korea south of the 38th parallel and establishing English as the official language during military control.[69] On 8 September US Lieutenant General John R. Hodge arrived in Incheon to accept the Japanese surrender south of the 38th parallel.[66] Appointed as military governor, Hodge directly controlled South Korea as head of the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK 1945–48).[70]

In December 1945, Korea was administered by a US–Soviet Union Joint Commission, as agreed at the Moscow Conference, with the aim of granting independence after a five-year trusteeship.[71][72] Waiting five years for independence was unpopular among Koreans, and riots broke out.[55] To contain them, the USAMGIK banned strikes on 8 December and outlawed the PRK Revolutionary Government and People's Committees on 12 December.[73] Following further civilian unrest,[74] the USAMGIK declared martial law.

Citing the inability of the Joint Commission to make progress, the US government decided[언제?] to hold an election under UN auspices to create an independent Korea. The Soviet authorities and Korean communists refused to co-operate on the grounds it would not be fair, and many South Korean politicians boycotted it.[75][76] The 1948 South Korean general election was held in May.[77][78] The resultant South Korean government promulgated a national political constitution on 17 July and elected Syngman Rhee as president on 20 July. The Republic of Korea (South Korea) was established on 15 August 1948.

In the Soviet Korean Zone of Occupation, the Soviets agreed to the establishment of a communist government[77] led by Kim Il Sung.[79] The 1948 North Korean parliamentary elections took place in August.[80] The Soviet Union withdrew its forces in 1948 and the US in 1949.[81][82]

제2차 국공내전

편집With the end of the war with Japan, the Chinese Civil War resumed in earnest between the Communists and the Nationalist-led government. While the Communists were struggling for supremacy in Manchuria, they were supported by the North Korean government with matériel and manpower.[83] According to Chinese sources, the North Koreans donated 2,000 railway cars worth of supplies while thousands of Koreans served in the Chinese PLA during the war.[84] North Korea also provided the Chinese Communists in Manchuria with a safe refuge for non-combatants and communications with the rest of China.[83]

The North Korean contributions to the Chinese Communist victory were not forgotten after the creation of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. As a token of gratitude, between 50,000 and 70,000 Korean veterans who served in the PLA were sent back along with their weapons, and they later played a significant role in the initial invasion of South Korea.[83] China promised to support the North Koreans in the event of a war against South Korea.[85]

대한민국 내 반란

편집By 1948, a North Korea-backed insurgency had broken out in the southern half of the peninsula. This was exacerbated by the undeclared border war between the Koreas, which saw division-level engagements and thousands of deaths on both sides.[86] The ROK was almost entirely trained and focused on counterinsurgency, rather than conventional warfare. They were equipped and advised by a force of a few hundred American officers, who were successful in helping the ROKA to subdue guerrillas and hold its own against North Korean military (Korean People's Army, KPA) forces along the 38th parallel.[87] Approximately 8,000 South Korean soldiers and police died in the insurgent war and border clashes.[88]

The first socialist uprising occurred without direct North Korean participation, though the guerrillas still professed support for the northern government. Beginning in April 1948 on Jeju Island, the campaign saw arrests and repression by the South Korean government in the fight against the South Korean Labor Party, resulting in 30,000 violent deaths, among them 14,373 civilians, of whom ~2,000 were killed by rebels and ~12,000 by ROK security forces. The Yeosu–Suncheon rebellion overlapped with it, as several thousand army defectors waving red flags massacred right-leaning families. This resulted in another brutal suppression by the government and between 2,976 and 3,392 deaths. By May 1949, both uprisings had been crushed.

Insurgency reignited in the spring of 1949 when attacks by guerrillas in the mountainous regions (buttressed by army defectors and North Korean agents) increased. Insurgent activity peaked in late 1949 as the ROKA engaged so-called People's Guerrilla Units. Organized and armed by the North Korean government, and backed by 2,400 KPA commandos who had infiltrated through the border, these guerrillas launched an offensive in September aimed at undermining the South Korean government and preparing the country for the KPA's arrival in force. This offensive failed.[89] However, the guerrillas were now entrenched in the Taebaek-san region of the North Gyeongsang Province and the border areas of the Gangwon Province.[90]

While the insurgency was ongoing, the ROKA and KPA engaged in battalion-sized battles along the border, starting in May 1949.[87] Border clashes between South and North continued on 4 August 1949, when thousands of North Korean troops attacked South Korean troops occupying territory north of the 38th parallel. The 2nd and 18th ROK Infantry Regiments repulsed attacks in Kuksa-bong,[91] and KPA troops were "completely routed".[92] Border incidents decreased by the start of 1950.[90]

Meanwhile, counterinsurgencies in the South Korean interior intensified; persistent operations, paired with worsening weather, denied the guerrillas sanctuary and wore away their fighting strength. North Korea responded by sending more troops to link up with insurgents and build more partisan cadres; North Korean infiltrators had reached 3,000 soldiers in 12 units by the start of 1950, but all were destroyed or scattered by the ROKA.[93]

On 1 October 1949, the ROKA launched a three-pronged assault on the insurgents in South Cholla and Taegu. By March 1950, the ROKA claimed 5,621 guerrillas killed or captured and 1,066 small arms seized. This operation crippled the insurgency. Soon after, North Korea made final attempts to keep the uprising active, sending battalion-sized units of infiltrators under the commands of Kim Sang-ho and Kim Moo-hyon. The first battalion was reduced to a single man over the course of engagements by the ROKA 8th Division. The second was annihilated by a two-battalion hammer-and-anvil maneuver by units of the ROKA 6th Division, resulting in a toll of 584 KPA guerrillas (480 killed, 104 captured) and 69 ROKA troops killed, plus 184 wounded.[94] By spring of 1950, guerrilla activity had mostly subsided; the border, too, was calm.[95]

전쟁의 서막

편집By 1949, South Korean and US military actions had reduced indigenous communist guerrillas in the South from 5,000 to 1,000. However, Kim Il Sung believed widespread uprisings had weakened the South Korean military and that a North Korean invasion would be welcomed by much of the South Korean population. Kim began seeking Stalin's support for an invasion in March 1949, traveling to Moscow to persuade him.[96]

Stalin initially did not think the time was right for a war in Korea. PLA forces were still embroiled in the Chinese Civil War, while US forces remained stationed in South Korea.[97] By spring 1950, he believed that the strategic situation had changed: PLA forces under Mao Zedong had secured final victory, US forces had withdrawn from Korea, and the Soviets had detonated their first nuclear bomb, breaking the US monopoly. As the US had not directly intervened to stop the communists in China, Stalin calculated they would be even less willing to fight in Korea, which had less strategic significance.[98] The Soviets had cracked the codes used by the US to communicate with their embassy in Moscow, and reading dispatches convinced Stalin that Korea did not have the importance to the US that would warrant a nuclear confrontation.[98] Stalin began a more aggressive strategy in Asia based on these developments, including promising economic and military aid to China through the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance.[99]

In April 1950, Stalin gave Kim permission to attack the government in the South, under the condition that Mao would agree to send reinforcements if needed.[100] For Kim, this was the fulfilment of his goal to unite Korea. Stalin made it clear Soviet forces would not openly engage in combat, to avoid a direct war with the US[100]

Kim met with Mao in May 1950 and differing historical interpretations of the meeting have been put forward. According to Barbara Barnouin and Yu Changgeng, Mao agreed to support Kim despite concerns of American intervention, as China desperately needed the economic and military aid promised by the Soviets.[101] Kathryn Weathersby cites Soviet documents which said Kim secured Mao's support.[102] Along with Mark O'Neill, she says this accelerated Kim's war preparations.[103][104] Chen Jian argues Mao never seriously challenged Kim's plans and Kim had every reason to inform Stalin that he had obtained Mao's support.[105]:112 Citing more recent scholarship, Zhao Suisheng contends Mao did not approve of Kim's war proposal and requested verification from Stalin, who did so via a telegram.[106]:28–9 Mao accepted the decision made by Kim and Stalin to unify Korea, but cautioned Kim over possible US intervention.[106]:30

Soviet generals with extensive combat experience from World War II were sent to North Korea as the Soviet Advisory Group. They completed plans for attack by May[107] and called for a skirmish to be initiated in the Ongjin Peninsula on the west coast of Korea. The North Koreans would then launch an attack to capture Seoul and encircle and destroy the ROK. The final stage would involve destroying South Korean government remnants and capturing the rest of South Korea, including the ports.[108]

On 7 June 1950, Kim called for a Korea-wide election on 5–8 August 1950 and a consultative conference in Haeju on 15–17 June. On 11 June, the North sent three diplomats to the South as a peace overture, which Rhee rejected outright.[100] On 21 June, Kim revised his war plan to involve a general attack across the 38th parallel, rather than a limited operation in Ongjin. Kim was concerned South Korean agents had learned about the plans and that South Korean forces were strengthening their defenses. Stalin agreed to this change.[109]

While these preparations were underway in the North, there were clashes along the 38th parallel, especially at Kaesong and Ongjin, many initiated by the South.[36][37] The ROK was being trained by the US Korean Military Advisory Group (KMAG). On the eve of war, KMAG commander General William Lynn Roberts voiced utmost confidence in the ROK and boasted that any North Korean invasion would merely provide "target practice".[110] For his part, Syngman Rhee repeatedly expressed his desire to conquer the North, including when US diplomat John Foster Dulles visited Korea on 18 June.[111]

Though some South Korean and US intelligence officers predicted an attack, similar predictions had been made before and nothing had happened.[112] The Central Intelligence Agency noted the southward movement by the KPA but assessed this as a "defensive measure" and concluded an invasion was "unlikely".[113] On 23 June UN observers inspected the border and did not detect that war was imminent.[114]

전력 비교

편집Chinese involvement was extensive from the beginning, building on previous collaboration between the Chinese and Korean communists during the Chinese Civil War. Throughout 1949 and 1950, the Soviets continued arming North Korea. After the communist victory in the Chinese Civil War, ethnic Korean units in the PLA were sent to North Korea.[115]

In the fall of 1949, two PLA divisions composed mainly of Korean-Chinese troops (the 164th and 166th) entered North Korea, followed by smaller units throughout the rest of 1949; these troops brought with them not only their experience and training, but also their weapons and other equipment, changing little but their uniforms. The reinforcement of the KPA with PLA veterans continued into 1950, with the 156th Division and several other units of the former Fourth Field Army arriving with their equipment in February; the PLA 156th Division was reorganized as the KPA 7th Division. By mid-1950, between 50,000 and 70,000 former PLA troops had entered North Korea, forming a significant part of the KPA's strength on the eve of the war's beginning.[116] The combat veterans and equipment from China, the tanks, artillery and aircraft supplied by the Soviets, and rigorous training increased North Korea's military superiority over the South, armed by the U.S. military with mostly small arms, but no heavy weaponry such as tanks.[117]

Several generals, such as Lee Kwon-mu, were PLA veterans born to ethnic Koreans in China. While older histories of the conflict often referred to these ethnic Korean PLA veterans as being sent from northern Korea to fight in the Chinese Civil War before being sent back, recent Chinese archival sources studied by Kim Donggill indicate that this was not the case. Rather, the soldiers were indigenous to China, as part of China's longstanding ethnic Korean community, and were recruited to the PLA in the same way as any other Chinese citizen.[118]

According to the first official census in 1949, the population of North Korea numbered 9,620,000,[119] and by mid-1950, North Korean forces numbered between 150,000 and 200,000 troops, organized into 10 infantry divisions, one tank division, and one air force division, with 210 fighter planes and 280 tanks, who captured scheduled objectives and territory, among them Kaesong, Chuncheon, Uijeongbu and Ongjin. Their forces included 274 T-34-85 tanks, 200 artillery pieces, 110 attack bombers, and some 150 Yak fighter planes, and 35 reconnaissance aircraft. In addition to the invasion force, the North had 114 fighters, 78 bombers, 105 T-34-85 tanks, and some 30,000 soldiers stationed in reserve in North Korea.[66] Although each navy consisted of only several small warships, the North and South Korean navies fought in the war as seaborne artillery for their armies.

In contrast, the South Korean population was estimated at 20 million,[120] but its army was unprepared and ill-equipped. As of 25 June 1950, the ROK had 98,000 soldiers (65,000 combat, 33,000 support), no tanks (they had been requested from the U.S. military, but requests were denied), and a 22-plane air force comprising 12 liaison-type and 10 AT-6 advanced-trainer airplanes. Large U.S. garrisons and air forces were in Japan,[121] but only 200–300 U.S. troops were in Korea.[122]

전쟁의 진행

편집폭풍 작전

편집At dawn on 25 June 1950, the KPA crossed the 38th parallel behind artillery fire.[123] It justified its assault with the claim ROK troops attacked first and that the KPA were aiming to arrest and execute the "bandit traitor Syngman Rhee".[124] Fighting began on the strategic Ongjin Peninsula in the west.[125][126] There were initial South Korean claims that the 17th Regiment had counterattacked at Haeju; some scholars argue the claimed counterattack was instead the instigating attack, and therefore that the South Koreans may have fired first.[125][127] However, the report that contained the Haeju claim contained errors and outright falsehoods.[128]

KPA forces attacked all along the 38th parallel within an hour. The KPA had a combined arms force including tanks supported by heavy artillery. The ROK had no tanks, anti-tank weapons or heavy artillery. The South Koreans committed their forces in a piecemeal fashion, and these were routed in a few days.[129]

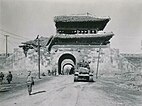

On 27 June, Rhee evacuated Seoul with some of the government. At 02:00 on 28 June the ROK blew up the Hangang Bridge across the Han River in an attempt to stop the KPA. The bridge was detonated while 4,000 refugees were crossing it, and hundreds were killed.[130][131] Destroying the bridge trapped many ROK units north of the river.[129] In spite of such desperate measures, Seoul fell that same day. Some South Korean National Assemblymen remained in Seoul when it fell, and 48 subsequently pledged allegiance to the North.[132]

On 28 June, Rhee ordered the massacre of suspected political opponents in his own country.[133] In five days, the ROK, which had 95,000 troops on 25 June, was down to less than 22,000 troops. In early July, when US forces arrived, what was left of the ROK was placed under US operational command of the United Nations Command.[134]

미국 개입의 요인

편집The Truman administration was unprepared for the invasion. Korea was not included in the strategic Asian Defense Perimeter outlined by United States Secretary of State Dean Acheson.[135] Military strategists were more concerned with the security of Europe against the Soviet Union, than East Asia.[136] The administration was worried a war in Korea could quickly escalate without American intervention. Diplomat John Foster Dulles stated in a cable: "To sit by while Korea is overrun by unprovoked armed attack would start a disastrous chain of events leading most probably to world war."[137]

While there was hesitance by some in the US government to get involved, considerations about Japan fed into the decision to engage on behalf of South Korea. After the fall of China to the communists, US experts saw Japan as the region's counterweight to the Soviet Union and China. While there was no US policy dealing with South Korea directly as a national interest, its proximity to Japan increased its importance. Said Kim: "The recognition that the security of Japan required a non-hostile Korea led directly to President Truman's decision to intervene ... The essential point ... is that the American response to the North Korean attack stemmed from considerations of U.S. policy toward Japan."[138][139]

Another consideration was the Soviet reaction if the US intervened. The Truman administration was fearful a Korean war was a diversionary assault that would escalate to a general war in Europe once the US committed in Korea. At the same time, "[t]here was no suggestion from anyone that the United Nations or the United States could back away from [the conflict]".[140] Yugoslavia—a possible Soviet target because of the Tito-Stalin split—was vital to the defense of Italy and Greece, and the country was first on the list of the National Security Council's post-North Korea invasion list of "chief danger spots".[141] Truman believed if aggression went unchecked, a chain reaction would start that would marginalize the UN and encourage communist aggression elsewhere. The UN Security Council approved the use of force to help the South Koreans, and the US immediately began using air and naval forces in the area to that end. The Truman administration still refrained from committing troops on the ground, because advisers believed the North Koreans could be stopped by air and naval power alone.[142]

The Truman administration was uncertain whether the attack was a ploy by the Soviet Union, or just a test of US resolve. The decision to commit ground troops became viable when a communiqué was received on 27 June indicating the Soviet Union would not move against US forces in Korea.[143] The Truman administration believed it could intervene in Korea without undermining its commitments elsewhere.

유엔 안보리 결의안

편집On 25 June 1950, the United Nations Security Council unanimously condemned the North Korean invasion of South Korea with Resolution 82. The Soviet Union, a veto-wielding power, had boycotted Council meetings since January 1950, protesting Taiwan's occupation of China's permanent seat.[144] The Security Council, on 27 June 1950, published Resolution 83 recommending member states provide military assistance to the Republic of Korea. On 27 June President Truman ordered U.S. air and sea forces to help. On 4 July the Soviet deputy foreign minister accused the U.S. of starting armed intervention on behalf of South Korea.[145]

The Soviet Union challenged the legitimacy of the war for several reasons. The ROK intelligence upon which Resolution 83 was based came from US Intelligence; North Korea was not invited as a sitting temporary member of the UN, which violated UN Charter Article 32; and the fighting was beyond the Charter's scope, because the initial north–south border fighting was classed as a civil war. Because the Soviet Union was boycotting the Security Council, some legal scholars posited that deciding upon this type of action required the unanimous vote of all five permanent members.[146][147]

Within days of the invasion, masses of ROK soldiers—of dubious loyalty to the Syngman Rhee regime—were retreating southwards or defecting en masse to the northern side, the KPA.[57]

미국의 대응

편집As soon as word of the attack was received,[148] Acheson informed Truman that the North Koreans had invaded South Korea.[149][150] Truman and Acheson discussed a US invasion response and agreed the US was obligated to act, comparing the North Korean invasion with Adolf Hitler's aggressions in the 1930s, and the mistake of appeasement must not be repeated.[151] US industries were mobilized to supply materials, labor, capital, production facilities, and other services necessary to support the military objectives of the Korean War.[152] Truman later explained he believed fighting the invasion was essential to the containment of communism as outlined in the National Security Council Report 68 (NSC 68):

Communism was acting in Korea, just as Hitler, Mussolini and the Japanese had ten, fifteen, and twenty years earlier. I felt certain that if South Korea was allowed to fall, Communist leaders would be emboldened to override nations closer to our own shores. If the Communists were permitted to force their way into the Republic of Korea without opposition from the free world, no small nation would have the courage to resist threat and aggression by stronger Communist neighbors.[153]

In August 1950, Truman and Acheson obtained the consent of Congress to appropriate $12 billion for military action, equivalent to $129 billion in 2022.[150] Because of the extensive defense cuts and emphasis on building a nuclear bomber force, none of the services were able to make a robust response with conventional military strength. General Omar Bradley, Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was faced with deploying a force that was a shadow of its World War II counterpart.[154][155]

Acting on Acheson's recommendation, Truman ordered MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Japan, to transfer matériel to the South Korean military, while giving air cover to evacuation of US nationals. Truman disagreed with advisers who recommended unilateral bombing of the North Korean forces and ordered the U.S. Seventh Fleet to protect Taiwan, whose government asked to fight in Korea. The US denied Taiwan's request for combat, lest it provoke retaliation from the PRC.[156] Because the US had sent the Seventh Fleet to "neutralize" the Taiwan Strait, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai criticized the UN and US initiatives as "armed aggression on Chinese territory".[157] The US supported the Kuomintang in Burma in the hope these KMT forces would harass China from the southwest, thereby diverting Chinese resources from Korea.[158](p. 65)

북한의 남진과 낙동강 방어선

편집The Battle of Osan, the first significant US engagement, involved the 540-soldier Task Force Smith, a small forward element of the 24th Infantry Division flown in from Japan.[159] On 5 July 1950, Task Force Smith attacked the KPA at Osan but without weapons capable of destroying KPA tanks. The KPA defeated the US, with 180 American casualties. The KPA progressed southwards, pushing back US forces at Pyongtaek, Chonan, and Chochiwon, forcing the 24th Division's retreat to Taejeon, which the KPA captured in the Battle of Taejon. The 24th Division suffered 3,602 dead and wounded and 2,962 captured, including its commander, Major General William F. Dean.[160]

By August, the KPA steadily pushed back the ROK and the Eighth United States Army southwards.[161] The impact of the Truman administration's defense budget cutbacks was keenly felt, as US troops fought costly rearguard actions. Facing a veteran and well-led KPA force, and lacking sufficient anti-tank weapons, artillery or armor, the Americans retreated and the KPA advanced down the Peninsula.[162][163] By September, UN forces were hemmed into a corner of southeast Korea, near Pusan. This 230-킬로미터 (140-마일) perimeter enclosed about 10% of Korea, in a line defined by the Nakdong River.

The KPA purged South Korea's intelligentsia by killing civil servants and intellectuals. On 20 August, MacArthur warned Kim Il Sung he would be held responsible for KPA atrocities.[164]

Kim's early successes led him to predict the war would finish by the end of August. Chinese leaders were more pessimistic. To counter a possible US deployment, Zhou secured a Soviet commitment to have the Soviet Union support Chinese forces with air cover, and he deployed 260,000 soldiers along the Korean border, under the command of Gao Gang. Zhou authorized a topographical survey of Korea and directed Lei Yingfu, Zhou's military adviser in Korea, to analyze the military situation. Lei concluded MacArthur would likely attempt a landing at Incheon.[165][166] After conferring with Mao that this would be MacArthur's most likely strategy, Zhou briefed Soviet and North Korean advisers of Lei's findings, and issued orders to PLA commanders to prepare for US naval activity in the Korea Strait.[167]

In the resulting Battle of Pusan Perimeter, UN forces withstood KPA attacks meant to capture the city at the Naktong Bulge, P'ohang-dong, and Taegu. The United States Air Force (USAF) interrupted KPA logistics with 40 daily ground support sorties, which destroyed 32 bridges, halting daytime road and rail traffic. KPA forces were forced to hide in tunnels by day and move only at night.[168] To deny military equipment and supplies to the KPA, the USAF destroyed logistics depots, refineries, and harbors, while U.S. Navy aircraft attacked transport hubs. Consequently, the overextended KPA could not be supplied throughout the south.[169] On 27 August, 67th Fighter Squadron aircraft mistakenly attacked facilities in Chinese territory, and the Soviet Union called the Security Council's attention to China's complaint about the incident.[170] The US proposed a commission of India and Sweden determine what the US should pay in compensation, but the Soviets vetoed this.[171][172]

Meanwhile, US garrisons in Japan continually dispatched soldiers and military supplies to reinforce defenders in the Pusan Perimeter.[173] MacArthur went so far as to call for Japan's rearmament.[174] Tank battalions deployed to Korea, from the port of San Francisco to the port of Pusan, the largest Korean port. By late August, the Pusan Perimeter had 500 medium tanks battle-ready.[175] In early September 1950, UN forces outnumbered the KPA 180,000 to 100,000 soldiers.[54][176]

인천 상륙 작전

편집Against the rested and rearmed Pusan Perimeter defenders and their reinforcements, the KPA were undermanned and poorly supplied; unlike the UN, they lacked naval and air support.[177] To relieve the Pusan Perimeter, MacArthur recommended an amphibious landing at Incheon, near Seoul, well over 160 km (100 mi) behind the KPA lines.[178] On 6 July, he ordered Major General Hobart R. Gay, commander of the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division, to plan an amphibious landing at Incheon; on 12–14 July, the 1st Cavalry Division embarked from Yokohama, Japan, to reinforce the 24th Infantry Division inside the Pusan Perimeter.[179]

Soon after the war began, MacArthur began planning an Incheon landing, but the Pentagon opposed him.[178] When authorized, he activated a combined US Army and Marine Corps, and ROK force. The X Corps, consisted of 40,000 troops of the 1st Marine Division, the 7th Infantry Division and around 8,600 ROK soldiers.[180] By 15 September, the amphibious force faced few KPA defenders at Incheon: military intelligence, psychological warfare, guerrilla reconnaissance, and protracted bombardment facilitated a light battle. However, the bombardment destroyed most of Incheon.[181]

낙동강 반격전

편집On 16 September Eighth Army began its breakout from the Pusan Perimeter. Task Force Lynch,[182][183] 3rd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, and 70th Tank Battalion units advanced through 171.2 km (106.4 mi) of KPA territory to join the 7th Infantry Division at Osan on 27 September.[179] X Corps rapidly defeated the KPA defenders around Seoul, thus threatening to trap the main KPA force.[184]

On 18 September, Stalin dispatched General H. M. Zakharov to advise Kim to halt his offensive around the Pusan Perimeter, and redeploy his forces to defend Seoul. Chinese commanders were not briefed on North Korean troop numbers or operational plans. Zhou suggested the North Koreans should attempt to eliminate the UN forces at Incheon only if they had reserves of at least 100,000 men; otherwise, he advised the North Koreans to withdraw their forces north.[185]

On 25 September, Seoul was recaptured by UN forces. US air raids caused heavy damage to the KPA, destroying most of its tanks and artillery. KPA troops in the south, instead of effectively withdrawing north, rapidly disintegrated, leaving Pyongyang vulnerable.[185] During the retreat, only 25,000-30,000 KPA soldiers managed to reach the KPA lines.[186][187] On 27 September, Stalin convened an emergency session of the Politburo, where he condemned the incompetence of the KPA command and held Soviet military advisers responsible for the defeat.[185]

유엔군의 38선 돌파

편집On 27 September, MacArthur received secret National Security Council Memorandum 81/1 from Truman reminding him operations north of the 38th parallel were authorized only if "at the time of such operation there was no entry into North Korea by major Soviet or Chinese Communist forces, no announcements of intended entry, nor a threat to counter our operations militarily".[188] On 29 September, MacArthur restored the government of the Republic of Korea under Syngman Rhee.[185] The Joint Chiefs of Staff on 27 September sent MacArthur a comprehensive directive: it stated the primary goal was the destruction of the KPA, with unification of the Peninsula under Rhee as a secondary objective "if possible"; the Joint Chiefs added this objective was dependent on whether the Chinese and Soviets would intervene, and was subject to changing conditions.[189]

On 30 September, Zhou warned the US that China was prepared to intervene if the US crossed the 38th parallel. Zhou attempted to advise KPA commanders on how to conduct a general withdrawal by using the same tactics that allowed Chinese communist forces to successfully escape Chiang Kai-shek's encirclement campaigns in the 1930s, but KPA commanders did not use these tactics effectively.[190] Bruce Cumings argues, however, that the KPA's rapid withdrawal was strategic, with troops melting into the mountains from where they could launch guerrilla raids on the UN forces spread out on the coasts.[191]

By 1 October the UN Command had repelled the KPA northwards past the 38th parallel; the ROK advanced after them into North Korea.[192] MacArthur made a statement demanding the KPA's unconditional surrender.[193] On 7 October, with UN authorization, the UN Command forces followed the ROK forces northwards.[194] The Eighth US Army drove up western Korea and captured Pyongyang on 19 October.[195] The 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team made their first of two combat jumps during the war, on 20 October at Sunchon and Sukchon. The mission was to cut the road north going to China, preventing North Korean leaders from escaping Pyongyang, and to rescue US prisoners of war.

At month's end, UN forces held 135,000 KPA prisoners of war. As they neared the Sino-Korean border, the UN forces in the west were divided from those in the east by 80–161 km (50–100 mi) of mountainous terrain.[196] In addition to the 135,000 captured, the KPA had suffered some 200,000 soldiers killed or wounded, for a total of 335,000 casualties since end of June 1950, and lost 313 tanks. A mere 25,000 KPA regulars retreated across the 38th parallel, as their military had collapsed. The UN forces on the peninsula numbered 229,722 combat troops (including 125,126 Americans and 82,786 South Koreans), 119,559 rear area troops, and 36,667 US Air Force personnel.[197] Taking advantage of the UN Command's strategic momentum against the communists, MacArthur believed it necessary to extend the war into China to destroy depots supplying the North Korean effort. Truman disagreed and ordered caution at the Sino-Korean border.[198]

중국인민지원군의 개입

편집On 3 October 1950, China attempted to warn the US, through its embassy in India, it would intervene if UN forces crossed the Yalu River.[199](p. 42)[105](p. 169) The US did not respond as policymakers in Washington, including Truman, considered it a bluff.[199](p. 42)[105](p. 169)[200](p. 57)

On 15 October Truman and MacArthur met at Wake Island. This was much publicized because of MacArthur's discourteous refusal to meet the president in the contiguous US.[201] To Truman, MacArthur speculated there was little risk of Chinese intervention in Korea,[202] and the PRC's opportunity for aiding the KPA had lapsed. He believed the PRC had 300,000 soldiers in Manchuria and 100,000–125,000 at the Yalu River. He concluded that, although half of those forces might cross south, "if the Chinese tried to get down to Pyongyang, there would be the greatest slaughter" without Soviet air force protection.[186][203]

Meanwhile on 13 October, the Politburo decided China would intervene even without Soviet air support, basing its decision on a belief superior morale could defeat an enemy that had superior equipment.[204] To that end, 200,000 Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) troops crossed the Yalu into North Korea.[205] UN aerial reconnaissance had difficulty sighting PVA units in daytime, because their march and bivouac discipline minimized detection.[206] The PVA marched "dark-to-dark" (19:00–03:00), and aerial camouflage (concealing soldiers, pack animals, and equipment) was deployed by 05:30. Meanwhile, daylight advance parties scouted for the next bivouac site. During daylight activity or marching, soldiers remained motionless if an aircraft appeared;[206] PVA officers were under orders to shoot security violators.[출처 필요] Such battlefield discipline allowed a three-division army to march the 460 km (286 mi) from An-tung, Manchuria, to the combat zone in 19 days. Another division night-marched a circuitous mountain route, averaging 29 km (18 mi) daily for 18 days.[66]

After secretly crossing the Yalu River on 19 October, the PVA 13th Army Group launched the First Phase Offensive on 25 October, attacking advancing UN forces near the Sino-Korean border. This decision made solely by China changed the attitude of the Soviet Union. Twelve days after PVA troops entered the war, Stalin allowed the Soviet Air Forces to provide air cover and supported more aid to China.[207] After inflicting heavy losses on the ROK II Corps at the Battle of Onjong, the first confrontation between Chinese and US military occurred on 1 November 1950. Deep in North Korea, thousands of soldiers from the PVA 39th Army encircled and attacked the US 8th Cavalry Regiment with three-prong assaults—from the north, northwest, and west—and overran the defensive position flanks in the Battle of Unsan.[208]

On 13 November, Mao appointed Zhou overall commander and coordinator of the war effort, with Peng Dehuai as field commander.[205] On 25 November, on the Korean western front, the PVA 13th Army Group attacked and overran the ROK II Corps at the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River, and then inflicted heavy losses on the US 2nd Infantry Division on the UN forces' right flank.[209] Believing they could not hold against the PVA, the Eighth Army began to retreat, crossing the 38th parallel in mid-December.[210]

In the east, on 27 November, the PVA 9th Army Group initiated the Battle of Chosin Reservoir. Here, the UN forces fared better: like the Eighth Army, the surprise attack forced X Corps to retreat from northeast Korea, but they were able to break out from the attempted encirclement by the PVA and execute a successful tactical withdrawal. X Corps established a defensive perimeter at the port city of Hungnam on 11 December and evacuated by 24 December, to reinforce the depleted Eighth Army to the south.[211][212] About 193 shiploads of UN forces and matériel (approximately 105,000 soldiers, 98,000 civilians, 17,500 vehicles, and 350,000 tons of supplies) were evacuated to Pusan.[213] The SS Meredith Victory was noted for evacuating 14,000 refugees, the largest rescue operation by a single ship, even though it was designed to hold 12 passengers. Before escaping, the UN forces razed most of Hungnam, with particular attention to the port.[186][214]

In early December UN forces, including the British Army's 29th Infantry Brigade, evacuated Pyongyang along with refugees.[215] Around 4.5 million North Koreans are estimated to have fled South or elsewhere abroad.[216] On 16 December Truman declared a national state of emergency with Proclamation No. 2914, 3 C.F.R. 99 (1953),[217] which remained in force until September 1978.[e] The next day, 17 December, Kim Il Sung was deprived of the right of command of KPA by China.[218]

38선 일대에서의 공방

편집A ceasefire presented by the UN to the PRC, after the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River on 11 December, was rejected by the China, which was convinced of the PVA's invincibility after its victory in that battle and the wider Second Phase Offensive.[219][220] With Lieutenant General Matthew Ridgway assuming command of the Eighth Army on 26 December, the PVA and the KPA launched their Third Phase Offensive on New Year's Eve. Using night attacks in which UN fighting positions were encircled and assaulted by numerically superior troops, who had the element of surprise, the attacks were accompanied by loud trumpets and gongs, which facilitated tactical communication and disoriented the enemy. UN forces had no familiarity with this tactic, and some soldiers panicked, abandoning their weapons and retreating to the south.[221] The offensive overwhelmed UN forces, allowing the PVA and KPA to capture Seoul for the second time on 4 January 1951.

These setbacks prompted MacArthur to consider using nuclear weapons against the Chinese or North Korean interiors, intending radioactive fallout zones to interrupt the Chinese supply chains.[222] However, upon the arrival of the charismatic General Ridgway, the esprit de corps of the bloodied Eighth Army revived.[223]

UN forces retreated to Suwon in the west, Wonju in the center, and the territory north of Samcheok in the east, where the battlefront stabilized and held.[221] The PVA had outrun its logistics capability and thus were unable to press on beyond Seoul as food, ammunition, and matériel were carried nightly, on foot and bicycle, from the border at the Yalu River to the three battle lines.[224] On 25 late January, upon finding that the PVA had abandoned their battle lines, Ridgway ordered a reconnaissance-in-force, which became Operation Thunderbolt.[225] A full-scale advance fully exploited the UN's air superiority,[226] concluding with the UN forces reaching the Han River and recapturing Wonju.[225]

Following the failure of ceasefire negotiations in January, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 498 on 1 February, condemning the PRC as an aggressor and calling upon its forces to withdraw from Korea.[227][228]

In early February, the ROK 11th Division ran an operation to destroy guerrillas and pro-DPRK sympathizers in the South Gyeongsang Province.[229] The division and police committed the Geochang and Sancheong–Hamyang massacres.[229] In mid-February, the PVA counterattacked with the Fourth Phase Offensive and achieved victory at Hoengseong. However, the offensive was blunted by US IX Corps at Chipyong-ni in the center.[225] The US 23rd Regimental Combat Team and French Battalion fought a short but desperate battle that broke the attack's momentum.[225] The battle is sometimes known as the "Gettysburg of the Korean War": 5,600 U.S., and French troops were surrounded by 25,000 PVA. UN forces had previously retreated in the face of large PVA/KPA forces instead of getting cut off, but this time, they stood and won.[230]

In the last two weeks of February 1951, Operation Thunderbolt was followed by Operation Killer, carried out by the revitalized Eighth Army. It was a full-scale, battlefront-length attack staged for maximum exploitation of firepower to kill as many KPA and PVA troops as possible.[225] Operation Killer concluded with US I Corps re-occupying the territory south of the Han River, and IX Corps capturing Hoengseong.[231] On 7 March the Eighth Army attacked with Operation Ripper, expelling the PVA and the KPA from Seoul on 14 March. This was the fourth and final conquest of the city in a year, leaving it a ruin; the 1.5 million pre-war population was down to 200,000 and people were suffering from food shortages.[231][187]

In late April, Peng sent his deputy, Hong Xuezhi, to brief Zhou in Beijing. What Chinese soldiers feared, Hong said, was not the enemy, but having no food, bullets, or trucks to transport them to the rear when they were wounded. Zhou attempted to respond to the PVA's logistical concerns by increasing Chinese production and improving supply methods, but these were never sufficient. Large-scale air defense training programs were carried out and the People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) began participating in the war from September 1951 onward.[232] The Fourth Phase Offensive had failed to match the achievements of the Second Phase or the limited gains of the Third Phase. The UN forces, after earlier defeats and retraining, proved much harder to infiltrate by Chinese light infantry than in previous months. From 31 January to 21 April, the Chinese suffered 53,000 casualties.[233]

On 11 April Truman relieved General MacArthur as supreme commander in Korea for [234] several reasons. MacArthur had crossed the 38th parallel in the mistaken belief the Chinese would not enter the war, leading to major allied losses. He believed the use of nuclear weapons should be his decision, not the president's.[235] MacArthur threatened to destroy China unless it surrendered. While MacArthur felt total victory was the only honorable outcome, Truman was more pessimistic about his chances once involved in a larger war, feeling a truce and orderly withdrawal could be a valid solution.[236] MacArthur was the subject of congressional hearings in May and June 1951, which determined he had defied the orders of the president and thus violated the US Constitution.[237] A popular criticism of MacArthur was he never spent a night in Korea and directed the war from the safety of Tokyo.[238]

Ridgway was appointed supreme commander, and he regrouped the UN forces for successful counterattacks,[239] while General James Van Fleet assumed command of the Eighth Army.[240] Further attacks depleted the PVA and KPA forces; Operations Courageous (23–28 March) and Tomahawk (23 March) (a combat jump by the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team) were joint ground and airborne infiltrations meant to trap PVA forces between Kaesong and Seoul. UN forces advanced to the Kansas Line, north of the 38th parallel.[241]

The PVA counterattacked in April 1951, with the Fifth Phase Offensive, with three field armies (700,000 men).[242] The first thrust of the offensive fell upon I Corps, which fiercely resisted in the Battle of the Imjin River (22–25 April) and Battle of Kapyong (22–25 April), blunting the impetus of the offensive, which was halted at the No-name Line north of Seoul.[243] Casualty ratios were grievously disproportionate; Peng had expected a 1:1 or 2:1 ratio, but instead, Chinese combat casualties from 22 to 29 April totaled between 40,000 and 60,000 compared to only 4,000 for the UN —a ratio between 10:1 and 15:1.[244] By the time Peng had called off the attack in the western sector on 29 April, the three participating armies had lost a third of their front-line combat strength within a week.[245] On 15 May the PVA commenced the second impulse of the spring offensive and attacked the ROK and U.S. X Corps in the east at the Soyang River. Approximately 370,000 PVA and 114,000 KPA troops had been mobilized, with the bulk attacking in the eastern sector, with about a quarter attempting to pin the I Corps and IX Corps in the western sector. After initial success, they were halted by 20 May and repulsed over the following days, with Western histories generally designating 22 May as the end of the offensive.[246][247]

At month's end, the Chinese planned the third step of the Fifth Phase Offensive (withdrawal), which they estimated would take 10-15 days to complete for their 340,000 remaining men, and set the date for the night of 23 May. They were caught off guard when the Eighth Army counterattacked and regained the Kansas Line on the morning of 12 May, 23 hours before the expected withdrawal.[248][249] The surprise attack turned the retreat into "the most severe loss since our forces had entered Korea"; between 16-23 May, the PVA suffered another 45,000 to 60,000 casualties before their soldiers managed to evacuate.[249] The Fifth Phase Offensive as a whole had cost the PVA 102,000 soldiers (85,000 killed/wounded, 17,000 captured), with significant losses for the KPA.[250]

The end of the Fifth Phase Offensive preceded the start of the UN May–June 1951 counteroffensive. During the counteroffensive, the US-led coalition captured land up to about 10 km (6 mi) north of the 38th parallel, with most forces stopping at the Kansas Line and a minority going further to the Wyoming Line. PVA and KPA forces suffered greatly, especially in the Chuncheon sector and at Chiam-ni and Hwacheon; in the latter sector alone the PVA/KPA suffered over 73,207 casualties, including 8,749 captured, compared to 2,647 total casualties of the IX Corps.[251]

The halt at the Kansas Line and offensive action stand-down began the stalemate that lasted until the armistice of 1953. The disastrous failure of the Fifth Phase Offensive (which Peng recalled as one of only four mistakes he made in his military career) "led Chinese leaders to change their goal from driving the UNF out of Korea to merely defending China's security and ending the war through negotiations".[252]

교착전

편집For the rest of the war, the UN and the PVA/KPA fought but exchanged little territory. Large-scale bombing of North Korea continued, and protracted armistice negotiations began on 10 July 1951 at Kaesong in the North.[253] On the Chinese side, Zhou directed peace talks, and Li Kenong and Qiao Guanghua headed the negotiation team.[232] Combat continued; the goal of the UN forces was to recapture all of South Korea and avoid losing territory.[254] The PVA and the KPA attempted similar operations and later effected military and psychological operations to test the UN Command's resolve to continue the war.

The sides constantly traded artillery fire along the front, with American-led forces possessing a large firepower advantage over Chinese-led forces. In the last three months of 1952 the UN fired 3,553,518 field gun shells and 2,569,941 mortar shells, while the communists fired 377,782 field gun shells and 672,194 mortar shells: a 5.8:1 ratio.[255] The communist insurgency, reinvigorated by North Korean support and scattered bands of KPA stragglers, resurged in the south. In the autumn of 1951, Eighth Army Commander General James Van Fleet ordered Major General Paik Sun-yup to break the back of guerrilla activity. From December 1951 to March 1952, ROK security forces claimed to have killed 11,090 partisans and sympathizers and captured 9,916 more.[88]

PVA troops suffered from deficient military equipment, logistical problems, overextended communication and supply lines, and the constant threat of UN bombers. These factors led to a rate of Chinese casualties far greater than casualties suffered by UN troops. The situation became so serious that in November 1951 Zhou called a conference in Shenyang to discuss the PVA's logistical problems. It was decided to accelerate construction of railways and airfields, to increase the trucks available to the army, and to improve air defense by any means possible. These commitments did little to address the problems.[256]

In the months after the Shenyang conference, Peng went to Beijing several times to brief Mao and Zhou about the heavy casualties and the increasing difficulty of keeping front lines supplied with basic necessities. Peng was convinced the war would be protracted and that neither side would be able to achieve victory in the near future. On 24 February 1952, the Military Commission, presided over by Zhou, discussed the PVA's logistical problems with members of government agencies. After government representatives emphasized their inability to meet the war demands, Peng shouted: "You have this and that problem... You should go to the front and see with your own eyes what food and clothing the soldiers have! Not to speak of the casualties! For what are they giving their lives? We have no aircraft. We have only a few guns. Transports are not protected. More and more soldiers are dying of starvation. Can't you overcome some of your difficulties?" The atmosphere became so tense Zhou was forced to adjourn the conference. Zhou called a series of meetings, where it was agreed the PVA would be divided into three groups, to be dispatched to Korea in shifts; to accelerate training of pilots; to provide more anti-aircraft guns to front lines; to purchase more military equipment and ammunition from the Soviet Union; to provide the army with more food and clothing; and to transfer the responsibility of logistics to the central government.[257]

With peace negotiations ongoing, the Chinese attempted a final offensive in the final weeks of the war to capture territory: on 10 June, 30,000 Chinese troops struck South Korean and U.S. divisions on a 13 km (8 mi) front, and on 13 July, 80,000 Chinese soldiers struck the east-central Kumsong sector, with the brunt of their attack falling on 4 South Korean divisions. The Chinese had success in penetrating South Korean lines but failed to capitalize, particularly when US forces responded with overwhelming firepower. Chinese casualties in their final major offensive (above normal wastage for the front) were about 72,000, including 25,000 killed compared to 14,000 for the UN (most were South Koreans, 1,611 were Americans).[258]

휴전 협상

편집The on-again, off-again armistice negotiations continued for two years,[259] first at Kaesong, then Panmunjom.[260] A problematic point was prisoner of war repatriation.[261] The PVA, KPA and UN Command could not agree on a system of repatriation because many PVA and KPA soldiers refused to be repatriated back to the north,[262] which was unacceptable to the Chinese and North Koreans.[263] A Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission was set up to handle the matter.[264]

On 29 November 1952 U.S. President-Elect Dwight D. Eisenhower went to Korea to learn what might end the war.[265] Eisenhower took office on 20 January 1953. Stalin died on 5 March. The new Soviet leaders, engaged in their internal power struggle, had no desire to continue supporting China's efforts and called for an end to the hostilities.[266] China could not continue without Soviet aid, and North Korea was no longer a major player. Armistice talks entered a new phase. With UN acceptance of India's proposed Korean War armistice,[267] the KPA, PVA and UN Command signed the armistice agreement on 27 July 1953. South Korean President Syngman Rhee refused to sign. The war ended at this point, even though there was no peace treaty.[268] North Korea nevertheless claims it won the war.[269][270]

Under the agreement, the belligerents established the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) which mostly follows the 38th parallel. In the eastern part, the DMZ runs north of the 38th parallel; to the west, it travels south of it. Kaesong, site of the initial negotiations, was in pre-war South Korea but is now part of North Korea. The DMZ has since been patrolled by the KPA and the ROK, with the US still operating as the UN Command.

Operation Glory was conducted from July to November 1954, to allow combatants to exchange their dead. The remains of 4,167 US Army and US Marine Corps dead were exchanged for 13,528 KPA and PVA dead, and 546 civilians dead in UN POW camps were delivered to the South Korean government.[271] After Operation Glory, 416 Korean War unknown soldiers were buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, on Oahu, Hawaii. Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) records indicate the PRC and North Korea transmitted 1,394 names, of which 858 were correct. From 4,167 containers of returned remains, forensic examination identified 4,219 individuals. Of these, 2,944 were identified as from the US, and all but 416 were identified by name.[272] From 1996 to 2006, North Korea recovered 220 remains near the Sino-Korean border.[273]

전쟁 이후 군사분쟁

편집The Armistice Agreement provided for monitoring by an international commission. Since 1953, the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission, composed of members from the Swiss[274] and Swedish[275] armed forces, has been stationed near the DMZ.

In April 1975, South Vietnam's capital of Saigon was captured by the People's Army of Vietnam. Encouraged by that communist success, Kim Il Sung saw it as an opportunity to invade South Korea. Kim visited China in April 1975 and met with Mao and Zhou to ask for military aid. Despite Pyongyang's expectations, Beijing refused to help North Korea in another war.[276]

Since the armistice, there have been incursions and acts of aggression by North Korea. From 1966 to 1969, many cross-border incursions took place in what has been referred to as the Korean DMZ Conflict or Second Korean War. In 1968, a North Korean commando team unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate South Korean president Park Chung Hee in the Blue House Raid. In 1976, the Korean axe murder incident was widely publicized. Since 1974, 4 incursion tunnels leading to Seoul have been uncovered. In 2010, a North Korean submarine torpedoed and sank the South Korean corvette 틀:ROKS, resulting in the deaths of 46 sailors.[277] Again in 2010, North Korea fired artillery shells on Yeonpyeong island, killing 2 military personnel and 2 civilians.[278]

After a new wave of UN sanctions, on 11 March 2013, North Korea claimed that the armistice had become invalid.[279] On 13 March, North Korea confirmed it ended the Armistice and declared North Korea "is not restrained by the North-South declaration on non-aggression".[280] On 30 March, North Korea stated it entered a "state of war" and "the long-standing situation of the Korean peninsula being neither at peace nor at war is finally over".[281] Speaking on 4 April, US Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel said that Pyongyang "formally informed" the Pentagon that it "ratified" the potential use of a nuclear weapon against South Korea, Japan and the US, including Guam and Hawaii.[282] Hagel stated the US would deploy the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense anti-ballistic missile system to Guam because of a credible and realistic nuclear threat.[283]

In 2016, it was revealed North Korea approached the US about conducting formal peace talks to end the war officially. While the White House agreed to secret peace talks, the plan was rejected because North Korea refused to discuss nuclear disarmament as part of the treaty.[284] In 2018, it was announced that North Korea and South Korea agreed to talk to end the conflict. They committed themselves to the complete denuclearization of the Peninsula.[285] North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and South Korean President Moon Jae-In signed the Panmunjom Declaration.[286] In September 2021, Moon reiterated his call to end the war formally, in a speech at the UN.[287]

사상자

편집About 3 million people died in the war, most civilians, making it perhaps the deadliest conflict of the Cold War era.[33][34][288][289][290] Samuel Kim lists the war as the deadliest conflict in East Asia—the region most affected by armed conflict related to the Cold War.[288] Though only rough estimates of civilian fatalities are available, scholars have noted that the percentage of civilian casualties in Korea was higher than World War II or the Vietnam War, with Bruce Cumings putting civilian casualties at 2 million and Guenter Lewy in the range of 2-3 million.[33][34]

Cumings states that civilians represent at least half the war's casualties, while Lewy suggests it may have gone as high as 70%, compared to his estimates of 42% in World War II and 30%–46% in Vietnam.[33][34] Data compiled by the Peace Research Institute Oslo lists just under 1 million battle deaths over the war and a mid-estimate of 3 million total deaths, attributing the difference to excess mortality among civilians from one-sided massacres, starvation, and disease.[291] Compounding this devastation for civilians, virtually all major cities on the Peninsula were destroyed.[34] In per capita and absolute terms, North Korea was the most devastated by the war. According to Charles K. Armstrong, the war resulted in the death of an estimated 12%–15% of the North Korean population (경 10 million), "a figure close to or surpassing the proportion of Soviet citizens killed in World War II".[120]

군대

편집South Korea reported some 137,899 military deaths and 24,495 missing, 450,742 wounded, 8,343 POW.[21] The US suffered 33,686 battle deaths, 7,586 missing,[292] along with 2,830 non-battle deaths. There were 17,730 other non-battle US military deaths that occurred outside Korea during the same period that were erroneously included as war deaths until 2000.[293][294] The US suffered 103,284 wounded in action.[295] UN losses, excluding those of the US or South Korea, amounted to 4,141 dead and 12,044 wounded in action.

American combat casualties were over 90% of non-Korean UN losses. US battle deaths were 8,516 up to their first engagement with the Chinese on 1 November 1950.[296] The first four months prior to the Chinese intervention were by far the bloodiest per day for US forces, as they engaged the well-equipped KPA in intense fighting. American medical records show that from July to October 1950, the army sustained 31% of the combat deaths it ultimately incurred in the entire 37-month war.[297] The US spent US$30 billion on the war.[298] Some 1,789,000 American soldiers served in the war, accounting for 31% of the 5,720,000 Americans who served on active duty worldwide from June 1950 to July 1953.[24]

Deaths from non-American UN militaries totaled 3,730, with another 379 missing.[21]

- 틀:나라자료 United Kingdom:

1,109 dead[299]

2,674 wounded[299]

179 MIA[21]

977 POW[21] - 틀:나라자료 Turkey:[21]

741 dead

2,068 wounded

163 MIA

244 POW - 틀:나라자료 Canada:

516 dead[300]

1,042 wounded[301]

1 MIA[21]

33 POW[302] - 틀:나라자료 Australia:[303]

339 dead

1,216 wounded

43 MIA

26 POW - 틀:나라자료 French Fourth Republic:[21]

262 dead

1,008 wounded

7 MIA

12 POW - 틀:나라자료 Kingdom of Greece[21]

192 dead

543 wounded

3 POW - 틀:나라자료 Colombia:[21]

163 dead

448 wounded

28 POW - 틀:나라자료 Thailand:[21]

129 dead

1,139 wounded

5 MIA[모호한 표현] - 틀:나라자료 Ethiopian Empire[21]

121 dead

536 wounded - 틀:나라자료 Netherlands:[21]

122 dead

645 wounded

3 MIA - 틀:나라자료 Belgium:[21]

101 dead

478 wounded

5 MIA

1 POW - 틀:나라자료 Third Philippine Republic:[304]

92 dead

299 wounded

97 MIA/POW - 틀:나라자료 Japan:[12]

79 dead - 틀:나라자료 Union of South Africa:[21]

34 dead

9 POW - 틀:나라자료 New Zealand:[304]

34 dead

299 wounded

1 MIA/POW - 틀:나라자료 Norway:[21]

3 dead - 틀:나라자료 Luxembourg:[21]

2 dead

13 wounded - 틀:나라자료 India:[305]

1 dead

Chinese sources reported that the PVA suffered 114,000 battle deaths, 21,000 deaths from wounds, 13,000 deaths from illness, 340,000 wounded, and 7,600 missing. 7,110 Chinese POWs were repatriated to China.[32] In 2010, the Chinese government revised their official tally of war losses to 183,108 dead (114,084 in combat, 70,000 deaths from wounds, illness and other causes) and 21,374 POW,[306] 25,621 missing.[307] Overall, 73% of Chinese infantry troops served in Korea (25 of 34 armies, or 79 of 109 infantry divisions, were rotated in). More than 52% of the Chinese air force, 55% of the tank units, 67% of the artillery divisions, and 100% of the railroad engineering divisions were sent to Korea as well.[308] Chinese soldiers who served in Korea faced a greater chance of being killed than those who served in World War II or the Chinese Civil War.[309] China spent over 10 billion yuan on the war (roughly US$3.3 billion), not counting USSR aid.[310] This included $1.3 billion in money owed to the Soviet Union by the end of it. This was a relatively large cost, as China had only 4% of the national income of the US.[32] Spending on the war constituted 34–43% of China's annual government budget from 1950 to 1953, depending on the year.[310] Despite its underdeveloped economy, Chinese military spending was the world's fourth largest globally for most of the war after that of the US, the Soviet Union, and the UK; however, by 1953, with the winding down of the Korean War and the escalation of the First Indochina War, French spending also surpassed Chinese spending by about a third.[311]

According to the South Korean Ministry of National Defense, North Korean military losses totaled 294,151 dead, 91,206 missing, and 229,849 wounded, giving North Korea the highest military deaths of any belligerent in absolute and relative terms.[312] The PRIO Battle Deaths Dataset gave a similar figure for North Korean military deaths of 316,579.[313] Chinese sources reported similar figures for the North Korean military of 290,000 "casualties" and 90,000 captured.[32] The financial cost of the war for North Korea was massive in direct losses and lost economic activity; the country was devastated by the cost of the war and the American strategic bombing campaign, which, among other things, destroyed 85% of North Korea's buildings and 95% of its power generation.[314] The Soviet Union suffered 299 dead, with 335 planes lost.[315]

The Chinese and North Koreans estimated that about 390,000 soldiers from the US, 660,000 soldiers from South Korea and 29,000 other UN soldiers were "eliminated" from the battlefield.[32] Western sources estimate the PVA suffered about 400,000 killed and 486,000 wounded, while the KPA suffered 215,000 killed, 303,000 wounded, and over 101,000 captured or missing.[316] Cumings cites a much higher figure of 900,000 fatalities among Chinese soldiers.[33]

민간인

편집According to the South Korean Ministry of National Defense, there were over 750,000 confirmed violent civilians deaths during the war, another million civilians were pronounced missing, and millions more ended up as refugees. In South Korea, some 373,500 civilians were killed, more than 225,600 wounded, and over 387,740 were listed as missing. During the first communist occupation of Seoul alone, the KPA massacred 128,936 civilians and deported another 84,523 to North Korea. On the other side of the border, 1,594,000 North Koreans were reported as casualties including 406,000 civilians reported as killed, and 680,000 missing. Over 1.5 million North Koreans fled to the South.[312]

특징

편집미국의 미흡한 준비

편집In postwar analysis of the unpreparedness of US forces deployed during the summer and fall of 1950, Army Major General Floyd L. Parks stated "Many who never lived to tell the tale had to fight the full range of ground warfare from offensive to delaying action, unit by unit, man by man ... [T]hat we were able to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat ... does not relieve us from the blame of having placed our own flesh and blood in such a predicament."[317]

By 1950, US Secretary of Defense Louis A. Johnson had established a policy of faithfully following Truman's defense economization plans and aggressively attempted to implement it, even in the face of steadily increasing external threats. He consequently received much of the blame for the initial setbacks and widespread reports of ill-equipped and inadequately trained military forces in the war's early stages.[318]

As an initial response to the invasion, Truman called for a naval blockade of North Korea and was shocked to learn that such a blockade could be imposed only "on paper" since the U.S. Navy no longer had the warships with which to carry out his request.[318][319] Army officials, desperate for weaponry, recovered Sherman tanks and other equipment from Pacific War battlefields and reconditioned them for shipment to Korea.[318] Army ordnance officials at Fort Knox pulled down M26 Pershing tanks from display pedestals around Fort Knox in order to equip the third company of the Army's hastily formed 70th Tank Battalion.[320] Without adequate numbers of tactical fighter-bomber aircraft, the Air Force took F-51 (P-51) propeller-driven aircraft out of storage or from existing Air National Guard squadrons and rushed them into front-line service. A shortage of spare parts and qualified maintenance personnel resulted in improvised repairs and overhauls. A Navy helicopter pilot aboard an active duty warship recalled fixing damaged rotor blades with masking tape in the absence of spares.[321]

U.S. Army Reserve and Army National Guard infantry soldiers and new inductees (called to duty to fill out understrength infantry divisions) found themselves short of nearly everything needed to repel the North Korean forces: artillery, ammunition, heavy tanks, ground-support aircraft, even effective anti-tank weapons such as the M20 3.5-inch (89 mm) "Super Bazooka".[322] Some Army combat units sent to Korea were supplied with worn-out, "red-lined" M1 rifles or carbines in immediate need of ordnance depot overhaul or repair.[323][324] Only the Marine Corps, whose commanders had stored and maintained their World War II surplus inventories of equipment and weapons, proved ready for deployment, though they still were woefully understrength,[325] as well as in need of suitable landing craft to practice amphibious operations (Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson had transferred most of the remaining craft to the Navy and reserved them for use in training Army units).[326]

기갑전

편집The initial assault by KPA forces was aided by the use of Soviet T-34-85 tanks.[327] A KPA tank corps equipped with about 120 T-34s spearheaded the invasion. These faced an ROK that had few anti-tank weapons adequate to deal with the T-34s.[328] Additional Soviet armor was added as the offensive progressed.[329] The KPA tanks had a good deal of early successes against ROK infantry, Task Force Smith, and the U.S. M24 Chaffee light tanks that they encountered.[330][331] Interdiction by ground attack aircraft was the only means of slowing the advancing KPA armor. The tide turned in favor of the UN forces in August 1950 when the KPA suffered major tank losses during a series of battles in which the UN forces brought heavier equipment to bear, including American M4A3 Sherman and M26 medium tanks, alongside British Centurion, Churchill and Cromwell tanks.[332]

The Incheon landings on 15 September cut off the KPA supply lines, causing their armored forces and infantry to run out of fuel, ammunition, and other supplies. As a result of this and the Pusan perimeter breakout, the KPA had to retreat, and many of the T-34s and heavy weapons had to be abandoned. By the time the KPA withdrew from the South, 239 T-34s and 74 SU-76 self-propelled guns were lost.[333] After November 1950, KPA armor was rarely encountered.[334]

Following the initial assault by the North, the Korean War saw limited use of tanks and featured no large-scale tank battles. The mountainous, forested terrain, especially in the eastern central zone, was poor tank country, limiting their mobility. Through the last two years of the war in Korea, UN tanks served largely as infantry support and mobile artillery pieces.[335]

해전

편집Because neither Korea had a significant navy, the war featured few naval battles. A skirmish between North Korea and the UN Command occurred on 2 July 1950; the U.S. Navy cruiser USS Juneau, the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Jamaica and the Royal Navy frigate HMS Black Swan fought four North Korean torpedo boats and two mortar gunboats, and sank them. USS Juneau later sank several ammunition ships that had been present. The last sea battle of the Korean War occurred days before the Battle of Incheon; the ROK ship PC-703 sank a North Korean minelayer in the Battle of Haeju Island, near Incheon. Three other supply ships were sunk by PC-703 two days later in the Yellow Sea.[336]

During most of the war, the UN navies patrolled the west and east coasts of North Korea, sinking supply and ammunition ships and denying the North Koreans the ability to resupply from the sea. Aside from very occasional gunfire from North Korean shore batteries, the main threat to UN navy ships was from magnetic mines. During the war, five U.S. Navy ships were lost to mines: two minesweepers, two minesweeper escorts, and one ocean tug. Mines and coastal artillery damaged another 87 U.S. warships.[337]

공중전

편집The war was the first in which jet aircraft played the central role in air combat. Once-formidable fighters such as the P-51 Mustang, F4U Corsair, and Hawker Sea Fury[338]—all piston-engined, propeller-driven, and designed during World War II—relinquished their air-superiority roles to a new generation of faster, jet-powered fighters arriving in the theater. For the initial months of the war, the P-80 Shooting Star, F9F Panther, Gloster Meteor, and other jets under the UN flag dominated the Korean People's Air Force (KPAF) propeller-driven Soviet Yakovlev Yak-9 and Lavochkin La-9s.[339][340] By early August 1950, the KPAF was reduced to only about 20 planes.[341]

The Chinese intervention in late October 1950 bolstered the KPAF with the MiG-15, one of the world's most advanced jet fighters.[339] The USAF countered the MiG-15 by sending over three squadrons of its most capable fighter, the F-86 Sabre. These arrived in December 1950.[342][343] The Soviet Union denied the involvement of their personnel in anything other than an advisory role, but air combat quickly resulted in Soviet pilots dropping their code signals and speaking over the radio in Russian. This known direct Soviet participation was a casus belli that the UN Command deliberately overlooked, lest the war expand to include the Soviet Union and potentially escalate into atomic warfare.[339]